Slavery is a central and indisputable fact of the nation’s past. But our failure to remember what really happened is more than mere forgetfulness

Slightly tucked away from Manchester’s main thoroughfares, in a quiet square that bears his name, there is a statue of Abraham Lincoln – as it happens, just outside the windows of the Guardian’s offices in the city where the newspaper was founded nearly 202 years ago.

Manchester acquired the sculpture by chance. It was meant to appear outside the Houses of Parliament in London, as a symbol of Anglo-American cooperation – until the American donors were riven by fighting over its “weird and deformed” depiction of the famously homely president, and a more “heroic” statue was sent in its stead.

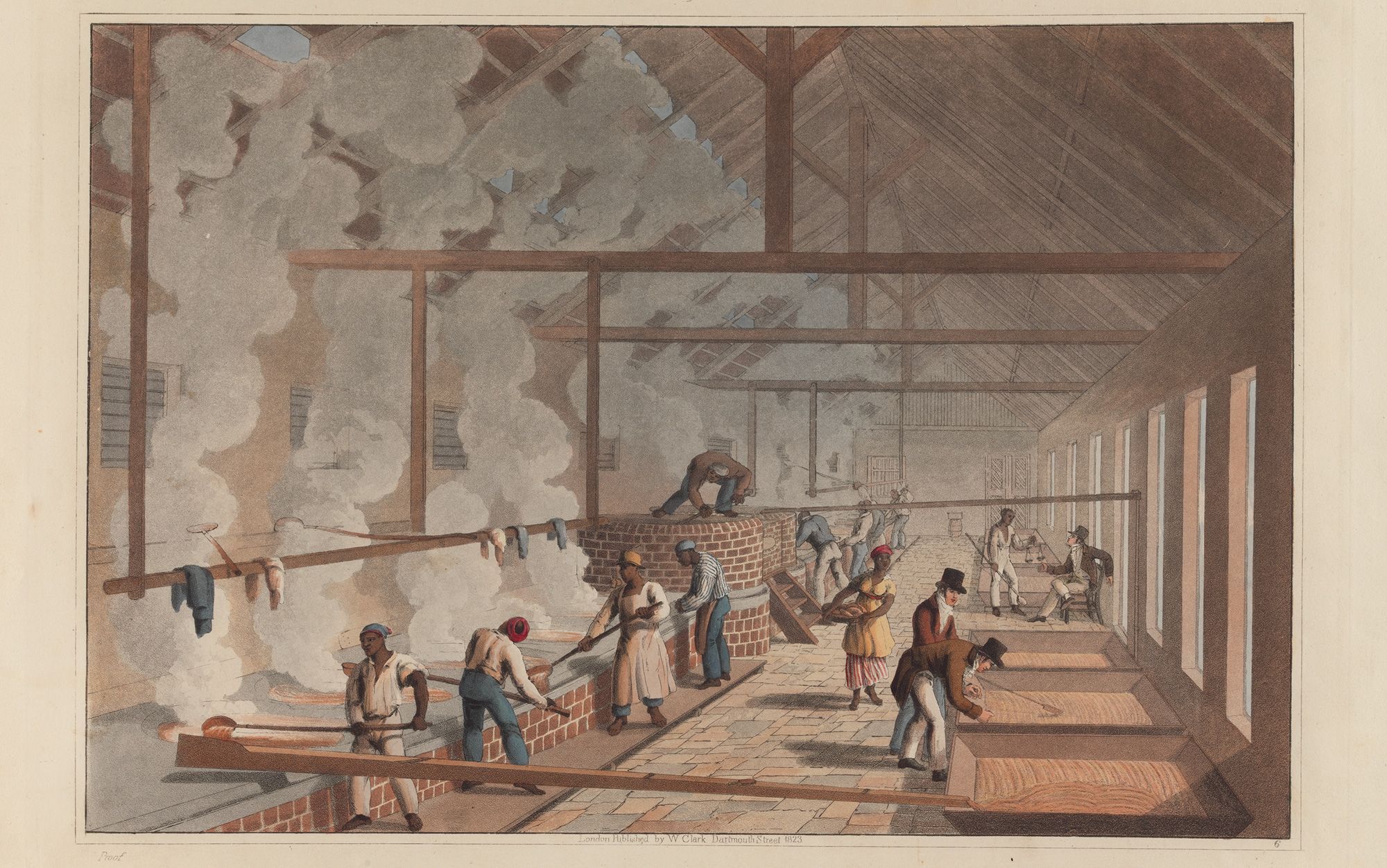

Manchester was keen to have it for a reason. Lincoln developed a deep affection for the city during the American civil war after Lancashire cotton mill workers resolved to back him at considerable cost to themselves. Manchester was the largest processor of cotton in the world at the time; the American slave-holding south was the largest producer. Lincoln, seeking to isolate and economically cripple the south, implemented a naval blockade of its cotton, which wrought great hardship on the mill workers in the north of England.

The British government was officially neutral. Many merchants in Liverpool, prioritising wealth at home over freedom abroad, backed the Confederate south and organised warships to support the enslavers. But in Manchester, a coalition of liberals, cotton workers and abolitionists came together to back the north. After a famous public meeting at the Free Trade Hall on 31 December 1862, Manchester’s workers resolved to endure the privations of the blockade and lend their weight to the fight against slavery. (The Guardian did not support them: its leader on that day warned that “English working men” should “know better than to allow the organised expression of their opinion as a class to be thrown into one scale or the other in a foreign civil war”.)

Months later, Lincoln wrote a letter of thanks to the “working-men of Manchester”, part of which is inscribed on his statue. “I know and deeply deplore the sufferings which the working-men of Manchester, and in all Europe, are called to endure in this crisis,” he wrote. “Under the circumstances, I cannot but regard your decisive utterances upon the question as an instance of sublime Christian heroism which has not been surpassed in any age or in any country.”

Manchester is understandably proud of this moment in its history, an act of international, antiracist solidarity between workers and enslaved African Americans. While in other cities statues of enslavers, slave traders and genocidal settlers have been defaced, dismantled or otherwise challenged, here was one statue that not only celebrated popular resistance to slavery but demonstrated a collective material sacrifice for the very principle.

Over time, the plaque on the statue featuring the words of Lincoln’s letter was faded by pollution and weather, and became impossible to read. When the local government minister Phil Woolas, then the Labour MP for nearby Oldham East and Saddleworth, was alerted to the problem, he resolved to pay “whatever it takes” to ensure its restoration. “It’s shameful, especially as we mark the 200th anniversary [of Britain abolishing the slave trade in 1807] that people cannot read this plaque,” Woolas said. The plaque was subsequently cleaned up. A few years later, Woolas was ousted from his seat by an electoral court after accusations of stirring up racial tensions to win votes.

But even as the workers’ support for the blockade showcased Manchester’s much-lauded liberal tradition, it also laid bare an essential feature of the city’s history that is rarely acknowledged: its economic dependence on the proceeds of slavery. For the reason the blockade affected Manchester so heavily was precisely because the labour of enslaved people was so deeply embedded in the wealth production that made Manchester and its surrounding areas what it was. It did not just put profits in the coffers of the merchants, it put food on the table of the labourers.

LEST WE REMEMBER HOW BRITAIN BURIED ITS HISTORY OF SLAVERY

Slavery in Britain existed before the Roman occupation and until the 11th century, when the Norman conquest of England resulted in the gradual merger of the pre-conquest institution of slavery into serfdom, and all slaves were no longer recognised separately in English law or custom. By the middle of the 12th century, the institution of slavery as it had existed prior to the Norman conquest had fully disappeared, but other forms of unfree servitude continued for some centuries.

Slavery in Britain 🇬🇧 & Beyond