“Things aren’t what they were” read the sign advertising Bob Dylan’s Rough and Rowdy Ways tour above the entrance to the London Palladium. The seasoned trickster has yet to meet an audience he doesn’t want to wrongfoot, but on this occasion the message was accurate. Changes have been made to the 81-year-old singer’s live act since his so-called Never Ending tour was forced off the road by the pandemic.

When it comes to style, Bob Dylan still gets it right

Even in his eighties, the enigmatic performer always looks elegant

Joan Baez was “wicked-looking — shiny black hair that hung down over the curve of slender hips, drooping lashes, partly raised”. A cook in a Greenwich Village café had “a fleshy, hard-bitten face, bulging cheeks, scars on his face like the marks of claws — thought of himself as a ladies’ man”. In Chronicles: Volume One, his 2004 memoir, Bob Dylan recalls in lyrical detail the appearance of people he met 40 years beforehand. It demonstrates an acute visual sensibility, though rarely does he turn that lens on himself.

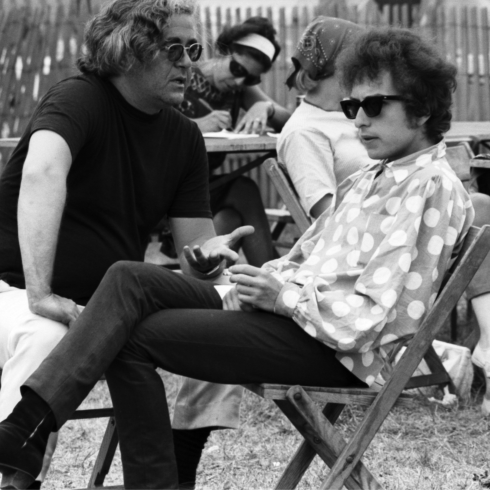

Bob Dylan with his manager Albert Grossman at the Newport Folk Festival in Rhode Island in 1965 © David Gahr/Getty Images

Dylan, now 81, has returned to the UK from October 19 to November 5 for a 12-date tour. He remains an enigma and gives few interviews, which leaves Dylanologists to study and debate his 60-year musical career (there is even an Institute for Bob Dylan Studies at the University of Tulsa). But rarely is Dylan considered in the context of his clothes, costume and visual identity.

We And yet, argues Lucas Hare, actor, Dylan superfan and co-host of the Is It Rolling, Bob? Talking Dylan podcast, it was Dylan who invented the rock-star look. “He was always at the centre of high fashion and yet existed outside of it,” says Hare. “Keith Richards, John Lennon, Jim Morrison — they all copied Dylan. And when that happened, he moved on pretty sharpish.”

Paul Gorman, author of The Look: Adventures in Rock & Pop Fashion, points to Dylan’s abrupt style change in the mid-1960s as the exact moment of invention. Take Dylan’s earnest, acoustic “spokesman of a generation” style on his 1962 debut album Bob Dylan — autumnal coat, peaked cap, a look borrowed from Woody Guthrie and quickly emulated by The Beatles.

When, in his early twenties, Dylan felt the pressure to lead a social movement was too great, that folksiness was swiftly replaced with the wiry, surreal and enigmatic creature he transformed himself into to mark 1965’s Bringing It All Back Home and his swerve to an electric backing band. “He’s saying, I’m no longer scuttling around in the American Dust Bowl because I’m not wearing the right clothes,” says Gorman. At his first appearance with that electric band at the Newport Folk Festival in 1965, Dylan is suddenly a rock star, an entirely different character, in polka-dot shirt, with crazy tall hair and hiding behind permanent sunglasses.

Here was a Dylan who was hard-edged and cartoonish, certainly Warhol-like (Dylan met the artist at roughly the same time), all served with a trace of the English dandy. It was not only a radical look, it was also hard to emulate. In the mid-1960s, there were few places to buy futuristic menswear.

Richard Young is now a well-known photographer, but in 1965 he was a teenage sales assistant in what was, he says, “the most elegant, campest menswear shop in London” — Sportique on Soho’s Old Compton Street, owned by the British menswear designer John Michael Ingram. It was, he says, one of just a handful of such boutiques in London. Young remembers serving Dylan and his entourage, who were on a visit to London and in search of Sportique’s shirts: colourful Swiss voile lace, or fly-front styles (as worn by Dirk Bogarde in the 1965 film Darling).

Sportique’s shirts were expensive and handmade by a tailor upstairs. The boutique also stocked sharp, covetable Italian and French imports not found elsewhere in London. (Gorman describes Sportique as “for men, not for boys”.)

“Dylan bought a suede maroon jacket made by a French fine leatherware company called Mac Douglas,” Young recalls. “The minute these jackets came into stock, they went.” (Young also says that, on the same day, he sold Bob Neuwirth, Dylan’s friend and assistant, the orange-and-white striped T-shirt he can be seen wearing behind Dylan on the cover of 1965’s Highway 61 Revisited.) Young was part of a generation of Londoners in awe of Dylan’s mid-1960s aesthetic. It was, he says, “a look that couldn’t be broken. Everyone tried to copy it. No one got it right.” Hare points out that Dylan’s mid-1960s look lasted long after Dylan ditched it, widely copied a decade later by punk-era performers such as John Cooper Clarke, among others.

Hare describes Dylan’s latter-day stage look — creole-style suits, pencil moustache, even spats — as “respectable country gentleman with roots in Nashville, a little carnivalesque, a little Clark Gable”. Says Young: “The way he dresses now is unique — a very stylish man in his eighties who knows about clothes and how to look and present himself on stage. I’ve never seen him in anything baggy. He’s always slim and he’s always elegant.” “There are few road maps for the older performer,” says Hare. “But he still gets it right.” Of course, Dylan is not there — he is a construct and a phantom. His real name is Robert Allen Zimmerman, a Jewish-American from Minnesota in the Midwest, not the southern Dust Bowl nor the streets of London or New York.

The real man remains largely an enigma. In Martin Scorsese’s 2019 film Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story, which explores Dylan’s 1975 tour of small US venues, Dylan says: “When somebody’s wearing a mask, he’s gonna tell you the truth. When he’s not wearing a mask, it’s highly unlikely.” Says Hare: “In that case, the only time he’s telling us the truth is on stage. Everything else is smoke and mirrors.”

Find out about our latest stories first — follow @financialtimesfashion on Instagram

The Philosophy of Modern Song — Bob Dylan’s world of sound

The singer-songwriter’s playlist of popular music is by turns folksy, grumpy, provocative and perceptive

Bob Dylan playing electric guitar at the Academy of Music in 1966 © Getty Images

When Bob Dylan published his superb memoir Chronicles: Volume 1 in 2004, he left dangling the tantalising promise of a sequel. But Volume 2 has yet to appear. Instead, the 2016 winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature has been occupied with a different book, which he has apparently been working on since 2010.

It is The Philosophy of Modern Song, a handsome-looking, weightily titled compendium in which the most significant singer-songwriter in the history of recorded music turns his attention to other artists’ songs, like a Dylanesque version of Sun Tzu’s The Art of War. There are 66 in total, each with its own chapter. Dylan writes about them in bursts of seemingly dashed-off prose that are optimistically labelled “essays” by the dust-jacket blurb.

There is no explanation why he has chosen these particular songs, nor what their shared philosophy might be. The 66 records symbolise a Highway 66 of mainly American popular music down which we jounce and bounce and swerve in a jalopy ridden at breakneck speed and no little eccentricity by our author.

The format is reminiscent of Dylan’s turn as a jive-talking disc jockey in his Theme Time Radio Hour series of radio programmes in the 2000s, whose producer gets a shout-out in the acknowledgments. The choice of songs is connoisseurial: I relished listening to them while reading the book.

Mirroring the musical direction of his recent albums, they are mainly drawn from a pre-British Invasion repertoire of country music, orchestral pop, rock ’n’ roll, doo-wop, blues and R&B. The earliest recording is a crackly 1924 bluegrass relic, Uncle Dave Macon’s “Keep My Skillet Good and Greasy”, which Dylan depicts as a proleptic blast of rock ’n’ roll.

Current acts are conspicuously absent. Fellow notables from the 1960s also get short shrift: The Who’s “My Generation” is the only classic from that era to be included. Dylan ignores its most arresting feature — the stuttered vocals, a lexical battering ram against the established order of things — and instead harrumphs about generational ingratitude.

His tone is variously jokey, hep, hard-boiled, folksy, grumpy and perceptive. Absurd truisms are invented (“As the old saying goes, an iceberg moves gracefully because most of it is beneath the surface”). Aphorisms are coined (“Art is a disagreement. Money is an agreement”). Wisecracks are tossed out, such as this droll description of outlaw country singer Johnny Paycheck: “Like a lot of small men, he was wrapped tighter than the inside of a golf ball and hit just about as often.” Free-wheeling glosses are given to song lyrics, tinged with surrealism. “You’re fairly certain you have become some kind of biological mutation, you are no longer a mere mortal”: this is Dylan’s unhinged interpretation of Domenico Modugno’s pop-operatic ditty “Volare”, the Italian entry in the 1958 Eurovision Song Contest. Some songs get more detailed commentary, others are dispatched in just a few sentences. The Drifters’ single “Saturday Night at the Movies” prompts such powerful feelings for old Hollywood that the song itself goes unmentioned.

That life was better in the old days is a repeatedly strummed chord. The chapter on “Feel So Good”, a ripsnorting 1950s rock ’n’ roller by Sonny Burgess, ends with Dylan giving Donald Trump’s Maga slogan a jitterbug somersault: “This is the sound that made America great.” His nostalgia is bolstered by scores of wittily chosen archive photos, which stylishly pad out the abbreviated passages of text. He has an incisive ability to get inside a song and make its workings understandable to those of us who have not, like him, composed more than 600 of them Chronicles showed how well Dylan can write about music. Although not always trustworthy as autobiography, in that respect it was revelatory. His generosity in thinking about other people’s songs has a doubled-edge quality, in that he has often been accused of making off with melodies and phrases for his own use.

But he has an incisive ability to get inside a song and make its workings understandable to those of us who have not, like him, composed more than 600 of them. “Take two people — one studies contrapuntal music theory, the other cries when they hear a sad song,” he writes while discussing Santana’s “Black Magic Woman”. “Which of the two really understands music better?”

The most generous moment in The Philosophy of Modern Song comes when he writes about a song called “Doesn’t Hurt Anymore” by the Native American musician and activist John Trudell, whose family was killed in an alleged arson attack in 1979. “Take a moment — read a little more about John Trudell than what is offered here,” Dylan writes. But there is a pronounced streak of ungenerosity in the book, and even cruelty. Only four female singers are included among the 66 acts. Women mostly turn up in The Philosophy of Modern Song as magnetic objects of attention in songs sung by men.

They throng its pages as a pulp-fiction line-up of “vamps”, “hellcats” and “foxy harlots”. The sexism is overblown to the point of comic absurdity, like the “thousands” of serpentine women that a delirious Dylan describes seeing dancing at Grateful Dead gigs: “Free floating, snaky and slithering like in a typical daydream.” But the imagery tips into outright misogyny in the chapter on The Eagles’ “Witchy Woman”, when the singer who dismissed Sigmund Freud as one of the “enemies of mankind” on his latest album Rough and Rowdy Ways is overwhelmed by a Freudian terror of the vagina dentata.

Johnnie Taylor’s R&B number “Cheaper to Keep Her” triggers a zany diatribe about divorce lawyers, which concludes with Dylan advocating polygamy and conjuring a bizarre vision of “women’s rights crusaders and women’s lib lobbyists” knocking “man back on his heels until he is pinned behind the eight ball dodging the shrapnel from the smashed glass ceiling”. A joke crawls out from the metaphorical wreckage; Dylan is having fun playing the curmudgeon. But the humour carries a sour tang.

The book’s unabashedly masculine slant shows scorn for what Dylan holds to be the milquetoast sensitivities of the modern age. “These people lack imagination and are fine throwing out the baby with the bathwater,” he comments, referring to those who denounce old films for “a two-minute sequence that changing times have rendered politically incorrect”.

The stance is designed to provoke, but it also traps Dylan in a dead-end of contrarianism and iconoclasm. Amid the entertaining sallies and insightful remarks is a mounting sense of meanness and pettiness. There are more things in modern songs — women’s voices, for instance — than are dreamt of in The Philosophy of Modern Song.

The Philosophy of Modern Song by Bob Dylan Simon & Schuster, £35/$45, 352 pages