It takes rare genius to provoke Bondi Iceberg Swimmers to express sympathy for MEdia Dragon, but the Redneck who invaded the pool on the weekend managed it ;-)

We all need a laugh from time to time, even if it's at our own expense

It's discouraging to make a mistake, but it's humiliating when you find out you're so unimportant that nobody noticed it.

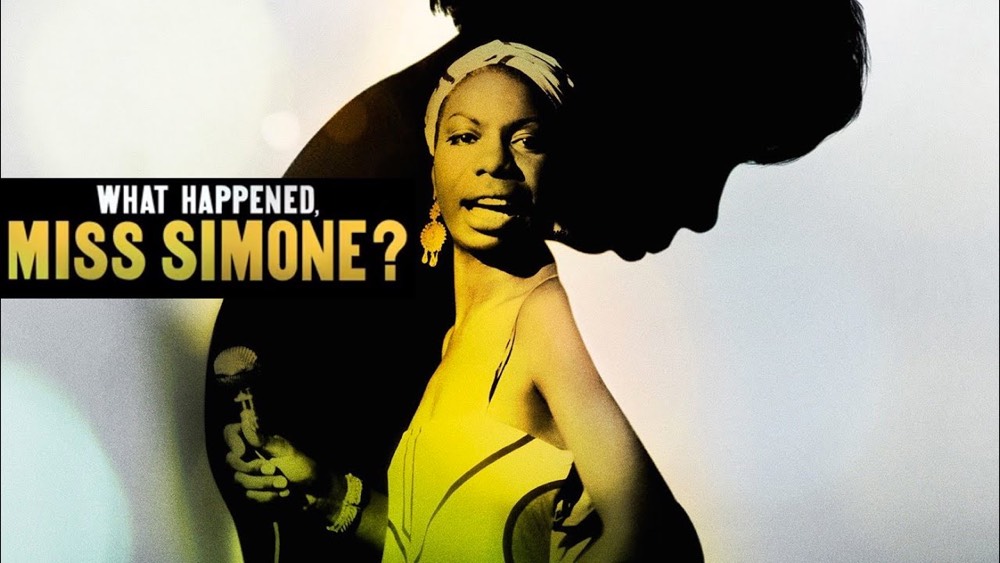

- Vocal is a type foundry that makes typefaces that highlight the history of underrepresented people “from the Women’s Suffrage Movement in Argentina to the Civil Rights Movement in America”. For example, the Martin typeface is based on signs carried by marchers in the streets of Memphis after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.

Netflix used Martin for What Happened Miss Simone?, Liz Garbus’ Nina Simone documentary:

Netflix used Martin for What Happened Miss Simone?, Liz Garbus’ Nina Simone documentary:

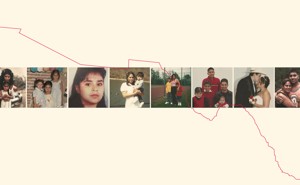

Mireya’s Third Crossing

The first time, she was raped. The second, she nearly drowned. In order to live in the United States legally, she had to leave her family and attempt to cross the border once more.

Must-Read Poetry: June 2019 - The Millions

Ocean Vuong Travels Back To The Hometown That Looms Large In His Novel

NPR reporter Kat Chow grew up near Vuong, and the two attended the same high school (though they never met each other there). She joins the poet-novelist on a road trip to Glastonbury, CT. – The Atlantic

Classic Fiction Is Confessional – Tell Your Secrets. But In The Social Media Age…

…what if the opposite is true? That your secrets, the things only you know about yourself, are in fact the most trivial, most banal things about you? In a society where many of us who don’t qualify as public figures spend a lot of time projecting our lives and our personalities in public, the biggest secret of all might be that, in whatever privacy we have left, we don’t have any secrets. – Book Forum

Axe-books of the year

A book must be the axe for the frozen sea inside us, says Kafka in the famous letter.

I wondered what this might mean as the 'books of the year' lists began to appear last month. Imagine if each contributor constrained themselves to choose only axe-books. Each entry would likely remain blank and the value of what did appear would be extreme compared to the predictable logrolling we see each year. Or maybe they would be exactly the same, as the idea of such a book is so vague that it could include everything from everyday escapist relief to a silent version of Freud's talking cure.

For this reason, it is the second most abused quotation of modern literature, after Beckett's Fail better. While Beckett is encouraging deeper failure rather than one that is closer to success, its playful ambiguity has enabled it to become a motivational mantra for a million creative writing memes, allowing Beckett one more catastrophe as he fails to turn budding writers away from the sewer of success. Kafka's line may not be misunderstood but is preceded by flourishes that rather complicate its promise:

My year of reading ended with four new books by or related to Maurice Blanchot, with one experienced with this kind of disappointment. I had been waiting twenty years for Christophe Bident's biography to be translated, as it promised a measure of the distance between Blanchot's life and his writing (what he discovered in writing). Several hundred pages later, the words Bident used to discuss key ideas and concepts became so light they floated free of any context that held any meaning for me: the absolute, the neuter, the unsayable, the avowable, the unavowable, the infinite, the impossible, the infinitely impossible. There is very little biographical detail, certainly not the trivia one might expect of the genre; his acquaintance with Brigitte Bardot as reported inL'Herne or the rumour that he learned Danish to read Kierkegaard in the original are not mentioned. As the book is a study of the work organised chronologically and written during Blanchot's lifetime, this is fair enough and mine is only an expression of disappointment and intellectual stupefaction. In reading hundreds of pages of commentary and analysis, I was reminded of Saul Bellow's narrator of Ravelstein who, when charged to read a philosophical article, felt like an ant who sets out to cross the Andes. Except, I was on the other side.

While it was no doubt disingenuous of me to hope for trivia from the life of this writer, there are two moments central to Blanchot's work in which the personal is exposed to the impersonal, suggesting there remains a navigable plain to be explored before the mountains rise up. Here is the first, in Ann Smock's translation of The Writing of the Disaster:

If the tears are evidence of an unfrozen sea, they are also evidence of disaster, grief and banishment, and so an experience much closer to Kafka's demands. And even if he is reading the sky and not a book, what happens then has the same ambiguous properties of reading, amplified here into a variety of religious experience; an experience that is repeated thirty years later.

The Instant of My Death describes how in the summer of 1944 a Nazi lieutenant ordered Blanchot out of the same house, perhaps to the same garden, to face a firing squad. As he awaits the order to fire, Blanchot writes that he experienced "a feeling of extraordinary lightness, a sort of beatitude (nothing happy, however)". Distracted by noise of fighting, the lieutenant leaves the scene and the firing squad tells Blanchot to nip off. Fifty years later, Blanchot speculates that what he felt was perhaps ecstacy, defined by the OED as "the state of being ‘beside oneself’ in ... anxiety, astonishment, fear, or passion" or "the withdrawal of the soul from the body [in a] mystic trance". But then Blanchot says it was rather the feeling "compassion for suffering humanity, the happiness of not being immortal or eternal", notable for being the opposite of the familiar literary pursuit of living forever.

I wondered what this might mean as the 'books of the year' lists began to appear last month. Imagine if each contributor constrained themselves to choose only axe-books. Each entry would likely remain blank and the value of what did appear would be extreme compared to the predictable logrolling we see each year. Or maybe they would be exactly the same, as the idea of such a book is so vague that it could include everything from everyday escapist relief to a silent version of Freud's talking cure.

For this reason, it is the second most abused quotation of modern literature, after Beckett's Fail better. While Beckett is encouraging deeper failure rather than one that is closer to success, its playful ambiguity has enabled it to become a motivational mantra for a million creative writing memes, allowing Beckett one more catastrophe as he fails to turn budding writers away from the sewer of success. Kafka's line may not be misunderstood but is preceded by flourishes that rather complicate its promise:

We ought to read only the kind of books that wound and stab us. We need the books that affect us like a disaster. We need books that grieve us deeply, like the death of someone we loved more than ourselves, like being banished into forests far from everyone, like a suicide.You can see why these words haven't become as popular. Yet as easily as such teenage-goth hyperbole is dismissed, the words do stir something beneath surface cynicism, which may be as slight as disappointment with everyday escapist relief, with Kafka's grim enthusiasm maintaining the promise of a future book that will allow us to bear the heaviest burdens without the lingering trauma, even if in doing so they retain the formula of disappointment: words that carry no weight.

My year of reading ended with four new books by or related to Maurice Blanchot, with one experienced with this kind of disappointment. I had been waiting twenty years for Christophe Bident's biography to be translated, as it promised a measure of the distance between Blanchot's life and his writing (what he discovered in writing). Several hundred pages later, the words Bident used to discuss key ideas and concepts became so light they floated free of any context that held any meaning for me: the absolute, the neuter, the unsayable, the avowable, the unavowable, the infinite, the impossible, the infinitely impossible. There is very little biographical detail, certainly not the trivia one might expect of the genre; his acquaintance with Brigitte Bardot as reported inL'Herne or the rumour that he learned Danish to read Kierkegaard in the original are not mentioned. As the book is a study of the work organised chronologically and written during Blanchot's lifetime, this is fair enough and mine is only an expression of disappointment and intellectual stupefaction. In reading hundreds of pages of commentary and analysis, I was reminded of Saul Bellow's narrator of Ravelstein who, when charged to read a philosophical article, felt like an ant who sets out to cross the Andes. Except, I was on the other side.

While it was no doubt disingenuous of me to hope for trivia from the life of this writer, there are two moments central to Blanchot's work in which the personal is exposed to the impersonal, suggesting there remains a navigable plain to be explored before the mountains rise up. Here is the first, in Ann Smock's translation of The Writing of the Disaster:

The Instant of My Death describes how in the summer of 1944 a Nazi lieutenant ordered Blanchot out of the same house, perhaps to the same garden, to face a firing squad. As he awaits the order to fire, Blanchot writes that he experienced "a feeling of extraordinary lightness, a sort of beatitude (nothing happy, however)". Distracted by noise of fighting, the lieutenant leaves the scene and the firing squad tells Blanchot to nip off. Fifty years later, Blanchot speculates that what he felt was perhaps ecstacy, defined by the OED as "the state of being ‘beside oneself’ in ... anxiety, astonishment, fear, or passion" or "the withdrawal of the soul from the body [in a] mystic trance". But then Blanchot says it was rather the feeling "compassion for suffering humanity, the happiness of not being immortal or eternal", notable for being the opposite of the familiar literary pursuit of living forever.