Like all of us, the overachieving, unfashionable NFL’s Cleveland Browns struggled to remain connected through the Pandemic. The players connected on Zoom by preparing – and institutionalising – the sharing of stories about their 4 H’s.

Heroes. History. Heartbreak. Hopes.

As we discussed in our December 12thpost, stories are the most powerful and impactful emotional tool leaders can use to connect in our ongoing remote / virtual / physical reality. Sharing stories builds empathy, understanding, trust and commitment. In the Browns example, the 4 H’s were an integral contribution to their 11-5 season, their best record in more than 20 years.

I’m using this myself now as 2022 feels like it will be off to a challenging start for all of us.

What Lois Lowry and Jozef Imrich Remember

The New Yorker: “Lowry, who has lost a sister and a son, has spent decades writing about the pains of memory. Literature, she says, is “a way that we rehearse life…

The title character of Lois Lowry’s most famous novel, “The Giver,” is an old man who guards all of human history and memory. The book’s protagonist, Jonas, is his apprentice. Jonas’s training involves withstanding the prismatic flood of the past—memories of joy and pain, war and suffering—so that his tightly regulated community can thrive in ignorance.

When the book came out, in 1993, Lowry had already won a fervent following. She received a Newbery Medal, in 1990, for “Number the Stars,” a novel about a Danish family resisting Nazi rule; her series featuring Anastasia Krupnik, a mischievous pre-teen in owlish glasses, charmed both grumpy older sisters and their parents. But “The Giver” remains her deepest achievement. Heaped with accolades, including another Newbery and a reputation as perhaps the best children’s novel ever written, it has sold more than twelve million copies.

It also landed on the American Library Association’s list of the most challenged books of the nineties. From the vantage of 2021, the novel is a double portent: a dystopian fantasy and an early spark in the tinderbox of the curriculum wars…”

Cold River: a survivor's story is about man's desire for freedom during a time when none existed. Jozef describes the village in which he grew up with such emotion and sadness that the reader can hear the snow crunching beneath his expectant mother's feet as she makes her way through the snow drifts. This story is fact, not fiction, when you are finished you will know what it is like to taste freedom for the first time. And perhaps feel pain of its cost.

Jozef Imrich: Why did you leave grandma?

Collection of Short Stories: ABCTales

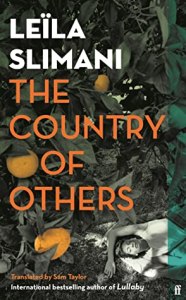

The Country of Others, by Leïla Slimani, translated by Sam Taylor

I’m not sure why I reserved this at the library; and I’m also not sure why I persisted with it when it was a bit of a slog to read. Was it because I’d never read anything set in Morocco before? Nope, I read four: Desert by Nobel Laureate JMG Le Clezio, translated by C. Dickson; The Storyteller of Marrakesh by Indian author Joydeep Roy-Battacharya; and two by Australian authors: Watch Out for Me by Sylvia Johnson, and Closer to Stone by Simon Cleary. Maybe it was because I thought it was time to read an author who was Moroccan?

I’m not sure why I reserved this at the library; and I’m also not sure why I persisted with it when it was a bit of a slog to read. Was it because I’d never read anything set in Morocco before? Nope, I read four: Desert by Nobel Laureate JMG Le Clezio, translated by C. Dickson; The Storyteller of Marrakesh by Indian author Joydeep Roy-Battacharya; and two by Australian authors: Watch Out for Me by Sylvia Johnson, and Closer to Stone by Simon Cleary. Maybe it was because I thought it was time to read an author who was Moroccan?

The blurb sounds interesting.

After the Liberation, Mathilde leaves France to join her husband in Morocco. But life here is unrecognisable to this brave and passionate young woman.

Suffocated by the heat of the Moroccan climate, by her loneliness on the farm, by the mistrust she inspires as a foreigner, and by their lack of money, Mathilde grows restless.

As violence threatens and Morocco’s own struggle for independence grows daily, Mathilde and Amine’s refusal to take sides sees them and their family at odds with their own desire for freedom. How can Mathilde — a woman whose life is dominated by the decisions of men — hold her family together in a world that is being torn apart?

The trouble is, it reads like the family history it is, turned into a rather long-winded novel. (There are 313 pages and this is only Volume One). The intent is worthy: Mathilde’s struggle for self-determination in a patriarchal society is an analogy with Morocco’s struggle against colonialism under the French. But it’s a messy analogy because Mathilde is French, and thus her desire for freedom comes from her French background and the independence that she had in the Resistance. Her ideas about feminism and autonomy come from an ‘external’ culture, and the implications of this are amplified by the extensive and often brutal commentary about how backward Morocco was in the postwar period when the novel is set.

Odd bits of detail are disconcerting: puzzling irrelevances break up the flow of the writing for no apparent purpose. This paragraph prefaces Mathilde intervention in her niece Selma’s rebellious behaviour.

When Mathilde reached the old hobnailed door, she grabbed the knocker and banged it twice, very hard. Yasmine opened it — she’d lifted up her skirts and Mathilde could see that her black calves were covered in curly hairs. It was almost ten in the morning but the house was quiet. She could hear the purring of the cats stretched out in the courtyard and the slop of the wet mop that the maid was using to clean the floor. Yasmine watched in astonishment as Mathilde took off her djellaba, tossed her headscarf onto a chair and ran upstairs. Yasmine coughed so hard that she spat a thick, greenish wad of mucus into the well. (p.90)

Apart from the fact that this is a bad case of Tell Everything, why does Yasmine lift up her skirts, and what are we meant to infer from the sight of those curly hairs? And how does Yasmine from the doorstep cough her disgusting mucus into the well?

Here’s another one, chosen at random:

(Previous paragraphs do not explain why she is not wearing her shoes when she arrives. Maybe she drove there barefoot?)

She put her shoes back on and climbed the stairs that led to the post office. A smiling woman greeted her at the counter. ‘Mulhouse, France,’ Mathilde explained. Next she headed to the main room, where the hundreds of post office boxes were located. Little brass doors, each one with a number on it, covered the high walls. She stopped next to box number 25: the same number as her year of birth, she’d said to Amine, who was always indifferent to this kind of remark. She took the little key out of her pocket and inserted it into the lock, but it didn’t turn. She took it out and put it in again but still nothing happened and the box wouldn’t open. Mathilde repeated the same actions with increasing impatience, and her annoyance was soon making people stare. Was this woman stealing letters sent to her husband by another woman? Or was she trying to take revenge on her lover by opening his post office box? An employee walked up to her slowly, like a zookeeper who had to return an animal to its cage. He was a very young man with red hair and a protruding jawline. Mathilde thought him ridiculous and ugly with his enormous feet and the pompous look on his face. (p.159)

Seriously, half a page about a key that doesn’t work? Describing post office boxes??

The Country of Others explores race, class, interpersonal conflict and domestic violence in the context of a mixed race marriage, and also ignorance, superstition and education in domestic and agricultural settings. The personal gets political when family members take different positions in the struggle against colonialism. But the story gets bogged down in superfluous detail and a narrative that seems hidebound by its origins in family history. I won’t be reading Volumes 2 and 3…

Other reviews: Tessa Hadley in The Guardian liked it more than I did. Mary O’Sullivan in the Irish Independent acknowledges that Slimani’s style takes a bit of getting used to…

Author: Leïla Slimani

Title: The Country of Others (le pays des autres)

Translated from the French by Sam Taylor

Publisher: Faber, 2021, first published 2020

ISBN: 9780571361625, pbk., 313 pages

Source: Bayside Library