Imrich’s nonfiction and Le Carré’s fiction of decline manage to speak to us all ... the ironies of characters like T...man and Low’s smart subordinate Baden Baden

Charm, patience, and a big budget for cognac and cigars: how John le Carré got sources to tell him everything

Half-angels fighting half-devils: the secret world of Le Canberra

I’ve been hearing the call of the dead. It’s been loud this week, following the death of David Cornwell, the writer known to the world as John le Carré. Ever since the news broke last Sunday, I’ve been devouring every obituary, reading every appreciation.

And that’s prompted a question. What is it exactly that we mourn when we mourn a public figure?

Le Carré's death touched me. It feels like the grownups are leaving the room

William Boyd remembers an exemplar of the ultimate literary professional, tirelessly writing at the top of his game well into his 80s

Le Carré was right

Christopher Tayler

I used to have a pet theory – outlined in the LRB in 2007 – to explain why John le Carré’s later stuff didn’t have, as I saw it, the lightning-in-a-bottle quality of the novels he wrote in the 1960s and 1970s. He had been wrongfooted by social change. More specifically, the declining pay and prestige of most kinds of public service meant that intelligence bureaucracies could no longer serve in the same way as a microcosm of the dark heart of the British establishment. Plummy chaps who, pre-Thatcher, would have made their way from prep schools, public schools and Oxbridge to the higher reaches of the BBC, the Civil Service or MI6– the chaps whose speech and behaviour le Carré had observed with an outsider-insider’s intentness when he was starting out – were overwhelmingly concentrated now in financial services and commercial law.

Perhaps, at the very heart of David Cornwell’s great and rich art — and double-edged appreciation — of deception was the choice of his pseudonym: John le Carré.

In the end, what makes Le Carré so great is his premise that our inner lives are perhaps best understood as a study in self-deception and self-revelation. That’s what middle age is about after all: moving through false views of yourself until you learn, somehow, that no single image can be correct. Not everything fits together. It’s not alright. But it’s what we have.

Perhaps it was appropriate that the news of a mass infiltration by insiders of Beijing’s ruling party should break in the same week that John le Carré died.

The passing of the master of spy stories reminded us all of times past, when the world was dominated by superpowers who employed tens of thousands to work in that shadowy space between diplomacy and sabotage; the arena of spooks and agents, doubles and triples.

Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy

Graham Greene called this the best spy story he had read and he’s not alone in that assessment. It’s about the hunt for a mole in the Secret Intelligence Service, known as the Circus. It follows on from a disastrous mission in Prague, not far from Cold War River, that results in the capture of a British agent. This is the novel in which Smiley really comes into his own and le Carre made the Cold War spy novel his own and in so doing captured the moral compromises and dismal practices seen on both sides of the Iron Curtain. Read this and follow it with the rest of the Smiley trilogy, The Honourable Schoolboy and Smiley's People.

During this pandemic summer that was no summer, with space constricted and time expanded, I found myself picking up John Le Carré’s 1963 spy novel, The Spy Who Came in From the Cold. I’d read the book decades ago, but my memory of the novel had been distilled into its closing final image—Alec Leamas and Liz Gold on the East German side of the Berlin Wall, two human beings trapped in the crosshairs of guns, searchlights, international intrigue, and institutional betrayal.

John le Carré Was a 21st Century Writer

Le Carré as a subversive anti-imperialist.

On his death, the establishment is patronising England’s great novelist as a Cold War figure, rather than confonting why he hated them.

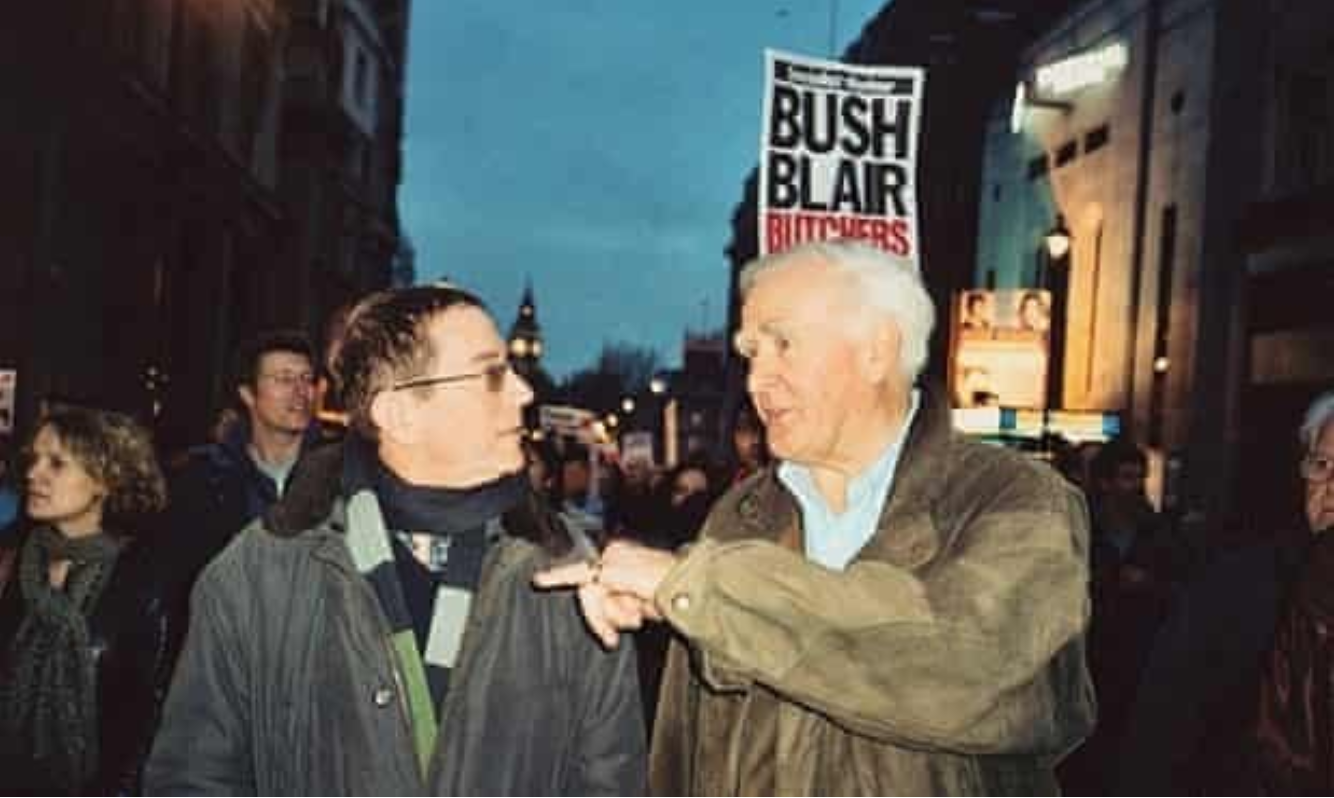

David Cornwell and Anthony Barnett demonstrating against President Bush’s visit to London, November 2003, photo Judith Herrin.

The David Cornwell that I knew, who is famous as John le Carré, is a twenty-first century writer, an author for our time and a forensic investigator of its ills.

Regarding the political insight of John le Carré (Obituary, 14 December), it was in the Guardian, in an interview with Stuart Jeffries (‘I do give a damn’, 6 October 2005), that Le Carré suggested that Britain might be sliding towards fascism. “Mussolini’s definition of fascism was that when you can’t distinguish corporate power from governmental power, you are on the way to a fascist state,” he said. This could not have been more vividly demonstrated than throughout the last nine months of 2020.

Nigel Gann

Lichfield, Staffordshire

John le Carré’s alien political, moral and Marek’s smarter data vision

Czech out article in the Financial Times: China pulls back from the world: rethinking Xi’s ‘project of the century.’ It discusses how China has substantially dialed down its once much-trumpeted Belt and Road initiative, in which it planned to fund massive infrastructure projects, largely along the former Silk Road, so as to provide land routes for exports and imports. It looked to be a geopolitical masterstroke, simultaneously reducing China’s exposure to having the US mess with China’s trade in the China Sea and other naval choke points; creating a co-dependency sphere (similar to what the US has with NATO) via directly funding important development projects in emerging economies.1

So what happened? The article keys off a recent report by Boston University’s Global Policy Development Center, titled Scope and Findings: China’s Overseas Development Finance Database. It has gotten some criticism (more on that shortly), but the Financial Times got confirmation of the thesis from multiple sources as well as other corroborating data points. So it’s reasonable to treat the Boston University account as directionally correct even though it arguably missed other funding channels that render its account less stark.

The high level recap of the Boston University report flags two major findings. The first is that China’s official development lending has fallen off sharply in recent years

Revealed: China suspected of spying on Americans via Caribbean phone networksGuardian. Resilc: “Sort of like Walmart, Amazon, Google, NYTimes, Fox, Home Depot?”

China Attempts to Cap Soaring Coal Prices as Imports Tumble Caixin

COLD WAR II: South China Sea: US warned Beijing of ‘major military breakthrough’ in bid to secure area.

“We’re shooting for early 2021 to be able to run a fleet battle problem that is centred on unmanned [technology].

“It will be on the sea, above the sea and under the sea as we get to demonstrate how we can align to the [U.S. Indo-Pacific Command] directives to use experimentation to drive lethality.”

The decision has been hailed as a “major breakthrough” for the US, according to Eurasiantimes.com.Training operations routinely occur in the waters, by all nations who lay claim to the region.

The US Navy regularly runs fleet battle problems, which allow the military to test how it would deploy its forces should conflict erupt.

It reportedly also wants around $2bn (£1.5bn) to produce 10 unmanned surface vessels during the next five years, a request Congress is currently raising objections about.