Intelligent people are just as prejudiced, but toward different groups

Bernard Arnault has been dubbed the Olympics’ godfather. Here’s how he built LVMH’s fortune AP

Barbora Seemanova and bizarre Kafjaeque sequence

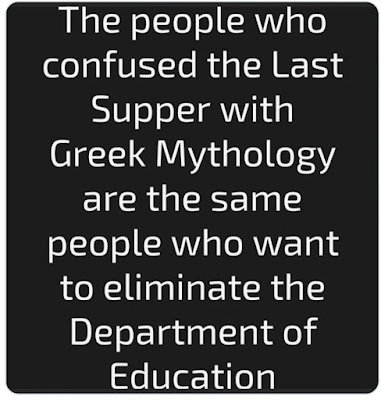

“Clearly there was never an intention to show disrespect to any religious group. [The opening ceremony] tried to celebrate community tolerance,” the Paris 2024 spokesperson Anne Descamps told a press conference. “We believe this ambition was achieved. If people have taken any offence we are really sorry.”

Kansas biologists find ‘super rare’ threatened species in the mouth of a hungry toad KSNT

11 Extraordinary Sharks That Live in Deep Sea WatersZME Science

How private equity tangled banks in a web of debt FT. Commentary: Private Equity Puts Debt EverywhereMatt Levine, Bloomberg

The Financial Consequences of Legalized Sports Gambling

Following a 2018 ruling of the U.S. Supreme Court, 38 states have legalized sports gambling. We study how this policy has impacted consumer financial health using the state-by-state rollout of legal sports gambling and a large and comprehensive dataset on consumer financial outcomes. Our main finding is that overall, consumers’ financial health is modestly deteriorating as the average credit score in states that legalize sports gambling decreases by roughly 0.3%. The decline in credit score is associated with changes in indicators of excessive debt. We find a substantial increase in bankruptcy rates, debt collections, debt consolidation loans, and auto loan delinquencies. We also find that financial institutions respond to the reduced creditworthiness of consumers by restricting access to credit. These results are stronger for states that allow sports gambling online compared to states that restrict access to in-person betting and larger for young men in low-income counties. Together, these results indicate that the ease of access to sports gambling is harming consumer financial health by increasing their level of debt.

That is from a new paper by Brett Hollenbeck, Poet Larsen, and Davide Proserpio.

Rupert Murdoch’s attempt to rule from the grave is stranger than fiction

Yet again, the Murdoch clan is demonstrating that truth can be stranger than fiction.

Wired [

webXray

unpaywalled]- This Machine Exposes Privacy Violations. A former Google engineer has built a search engine, WebXray, that aims to find illicit online data collection and tracking—with the goal of becoming “the Henry Ford of tech lawsuits.”…It’s a search engine for rooting out specific privacy violations anywhere on the web. By searching for a specific term or website, you can use WebXray to see which sites are tracking you, and where all that data goes. Its mission, he says, is simple; “I want to give privacy enforcers equal technology as privacy violators.” To level the playing field.

webXray – Privacy is inevitable: “webXray is a specialized tool for finding privacy violations on the web. While it shares similarities with a typical search engine like Google or Bing, its purpose, and features, are geared towards professionals in the legal and compliance sector who need to find specific violations of privacy law.

The best way to approach webXray is to first come up with some category of protected data you are interested in, many of which are defined by laws referenced in our knowledge base. Once you have an idea of what you are looking for – be it violations of children’s privacy, medical privacy, or other such topics – you are ready to begin a search. Each field below has text to help guide your use of the search engine.”