NSW Mental Health Commission faces complaints of ‘toxic workplace culture’

By Caitlin Fitzsimmons

A NSW government body responsible for improving the state’s mental health and wellbeing is scrambling to contain the fallout from a disastrous employee survey that revealed it is one of the unhappiest workplaces in the public service.

Staff at the Mental Health Commission of NSW have blown the lid on what they claim to be a toxic workplace culture plagued by bullying and micromanagement, while the plummeting morale is captured in this year’s latest People Matters NSW Public Sector Employee Survey.

Plummeting morale

Percentage of staff who would recommend their organisation as a great place to work

The NSW public sector has had the percentage of staff who would recommend their organisation as a great place to work grow from 60 per cent in 2016 to 63 per cent in 2023.

The equivalent score for the NSW Mental Health Commission has fallen from 74 per cent to 38 per cent.

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

2021

2022

2023

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

NSW public sectorMental Health Commission of NSW

Note: The health cluster did not conduct the annual employee survey in 2020.

Source: NSW Public Sector Employee Surveys 2016-2023

It comes after revelations earlier this year about similar problems at the National Mental Health Commission and the Queensland counterpart, and amid broader fears the independent statutory bodies designed to drive strategic reform of mental health services have grown too close to governments to be effective.

The Herald has spoken to five current or former employees of varying seniority who have spoken out in the hope of sparking change, with several describing the commission as “the worst workplace [they’ve] ever experienced”.

While the Herald has verified their identities, they all requested anonymity because of fear of retribution or the consequences of being known as a whistleblower in the public service.

As one staff member put it: “The commission has a widespread and well-known poor and toxic culture and there is a joke amongst employees that if you didn’t have a mental health condition before working there, you will after, and sadly in most cases this is true, [as I’ve] seen many people destroyed by their experiences at the commission.”

NSW Mental Health Minister Rose Jackson is on leave, but her spokesperson said:

“The NSW government expects every workplace, but especially those tasked with the mental health of people in our state to be treating people with respect and creating a safe and inclusive workplace.”

NSW Mental Health Minister Rose Jackson is on leave.

NSW Mental Health Minister Rose Jackson is on leave.CREDIT: ALEX ELLINGHAUSEN

A statutory review of the commission is due next year.

The commission is one of the public sector’s smaller workplaces, with 31 staff. The survey conducted in August and September reveal the NSW commission has a staff wellbeing score of 46 per cent, the worst result in the health cluster besides NSW Ambulance, and is the ninth unhappiest agency in the state out of more than 100.

Only 38 per cent of staff at the commission would recommend it as a great place to work, down from 74 per cent in 2016 and 2017.

The benchmark for the NSW public service is 63 per cent.

Thirty-seven per cent of commission employees intend to leave the organisation within a year, compared with 8 per cent for the public sector overall.

The average score for all questions was 55 per cent, ahead of NSW Ambulance and some local health districts delivering frontline services, but behind other office-based agencies such as the Ministry of Health with 72 per cent.

The poor results prompted a series of “town hall meetings” with staff in October, November and December, led by HR specialists from public sector agency HealthShare NSW.

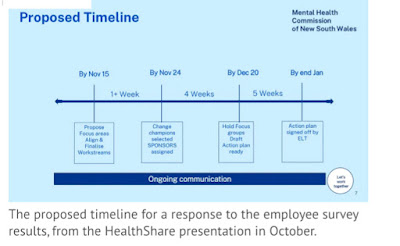

The HealthShare presentation from October included a timeline to develop an action plan to respond to the results by the end of January.

The process was met with scepticism by disillusioned staff who questioned HealthShare’s independence.

Screenshots obtained by the Herald show anonymous staff comments and the number of up-votes by colleagues, including key concerns about “psychological safety” for individuals sharing feedback, and suspicion this was a “predetermined process talking at us, not with us”.

Staff questioned why HealthShare had identified priorities before talking to staff, while ignoring other questions with low scores, and why the free-text responses in the original survey were not shared.

The proposed timeline for a response to the employee survey results, from the HealthShare presentation in October.

The proposed timeline for a response to the employee survey results, from the HealthShare presentation in October.

A HealthShare spokesperson said the agency was assisting the commission with the “routine planning of activities” relating to the annual survey. When it was put to HealthShare that the agency was not always involved after previous surveys, it declined to comment.

The NSW Mental Health Commissioner Catherine Lourey joined the organisation in 2015 and has been commissioner since 2017. Former Mental Health Minister Bronnie Taylor reappointed Lourey to a second five-year term last year.

Lourey declined to speak to the Herald.

Similar problems at the National Mental Health Commission were raised earlier this year, prompting federal Health Minister Mark Butler to launch a review. The review, which led to the resignation of chief executive Christine Morgan in September, found the organisation had a poor workplace culture and significant budget operating losses, but did not substantiate claims of bad administration and bullying.

The Working for Queensland survey published in August found similar staff dissatisfaction at the Queensland Mental Health Commission.

NSW Mental Health Commissioner Christine Lourey was reappointed for a second five-year term last year.

NSW Mental Health Commissioner Christine Lourey was reappointed for a second five-year term last year.CREDIT: WOLTER PEETERS

The most consistent complaint from NSW commission staff who spoke to the Herald was “micromanagement”, such as an expectation to “reply all” on every email and repeated checking of basic tasks.

Some people alleged that part-time staff seemed to be sidelined, and there was not enough consideration given to employees with lived experience of mental illness.

Several staff made claims of “bullying” or outlined issues that could amount to bullying, including managers being openly disrespectful to staff in meetings, changing the goalposts on projects without notice, and removing people who raised concerns from projects, sometimes without telling them.

“We live in fear,” one staff member said.

Workplaces with the lowest wellbeing scores in NSW government

Public secondary schools: 33 per cent

Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions: 34 per cent

NSW Ambulance: 39 per cent

NSW Police Force: 42 per cent

Public primary schools: 43 per cent

NSW Trustee and Guardian: 44 per cent

Greyhound Welfare and Integrity Commission: 45 per cent

Department of Education: 45 per cent

Mental Health Commission: 46 per cent

Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences: 47 per cent.

NSW Rural Fire Service: 47 per cent

A former senior employee said the broader question was whether the commission was effective, saying:

“I don’t know what the commission has achieved besides giving people in the mental health sector something to put on their CV.”

The legislation gives the commission the power to initiate its own reports and table them to parliament without approval from the minister.

Yet, several employees said there was some reluctance for the commission to speak out on important issues in order to “not rock the boat”, and it was regarded as routine for NSW Health to “massage” submissions authored by the commission.

This contributed to low staff morale because staff arrived wanting to make a difference, but quickly became disillusioned with the impact of their work.

A NSW Health spokesperson rejected the claim that it routinely “massaged” the commission’s reports or submissions.

“The Mental Health Commission has been established under its own legislation and NSW Health respects its role and independence,” the spokesperson said.

Dr Sebastian Rosenberg, from the University of Sydney’s Brain and Mind Centre, helped set up the NSW commission in 2012.

He said the organisation was “designed with teeth but [he] hadn’t seen any evidence it was using those teeth”, and all mental health commissions in Australia were “too timid”.

Rosenberg has an upcoming journal article evaluating the effectiveness of mental health commissions in Australia. The Western Australian commission established in 2010 is the oldest, and there are now equivalents in all states and territories except Tasmania and the Northern Territory, plus the national body.

“About a decade ago, Australia took a punt on this model of reform, with a view to breaking what was seen to be a logjam in mental health reform,” Rosenberg said. “So far, it is really difficult to see evidence that these commissions have been effective in breaking that logjam.”

Rosenberg measured the commissions’ effectiveness against metrics such as delivering more services or funding, or making the voice of consumers and carers more clearly heard.

He said it was a “damning indictment” of commissions that they hadn’t made it any easier to determine if the current approach was helping people.

!

KNOW MORE?

Tell us what you know about this story

Need to send tips securely?

Professor Alan Rosen, a community psychiatrist with academic appointments at Universities of Sydney and Wollongong, was on the taskforce to set up the NSW commission and also inaugural deputy commissioner until 2015.

Rosen said the potential of mental health commissions to drive strategic reform was immense, as demonstrated overseas, and he wanted to see them “built up” rather than “torn down”.

This required the commissions to act at “arm’s length from government”. Instead, Rosen said, commissions were “too cosy” with health departments, risking them becoming “compliant shadow bureaucracies”.

“What’s happened in Australia is that some reform-oriented commissions are too close to government and are often preoccupied with tasks assigned to them by government, and that doesn’t encourage them to undertake independent inquiries, providing frank scrutiny and advice,” Rosen said.

Rosen said mental health in NSW was historically poorly funded, especially for community services.

To address this, the NSW commission was meant to have “unfettered access to NSW Health data” to ensure all government funds allocated to mental health are actually spent in mental health.

Rosen said it appears this had not happened, which amounted to “a breach of promise by successive NSW governments and NSW health administrations over many years”.

The NSW commission did not answer extensive questions, but provided a statement from a spokesperson acknowledging the importance of the survey results.

“The survey showed there are areas that need collaborative effort to improve workplace satisfaction and employee engagement,” the spokesperson said. “We are looking at these very closely and working hard to improve the organisation.”