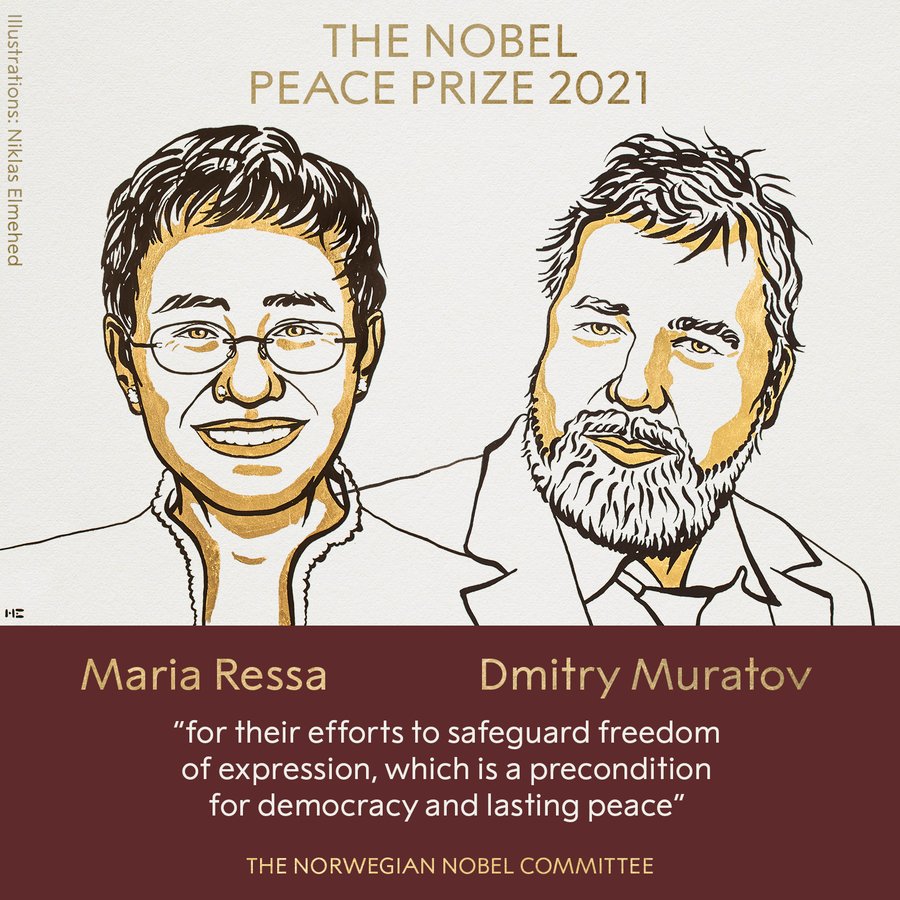

The Norwegian Nobel Committee has decided to award the 2021 Nobel Peace Prize to Maria Ressa and Dmitry Muratov for their efforts to safeguard freedom of expression, which is a precondition for democracy and lasting peace.

Journalists Maria Ressa, of the Philippines, and Dmitry Muratov, of Russia, have won this year’s Nobel Peace Prize, recognised “for their efforts to safeguard freedom of expression”, which the prize-giving committee described as being under threat worldwide

The two were given the prestigious award “for their courageous fight for freedom of expression in the Philippines and Russia,” Berit Reiss-Andersen, chair of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, said

Maria Ressa Just Won A Nobel – Only The 18th Woman In 126 Years To Win

Australian Voices - Trying to Make Positive Impact

How private management consultants took over the public service

On June 7, global management consulting firm McKinsey and Company was awarded a $1.4 million contract by the Department of Employment for work on a cross-government initiative examining labour force gaps in the Australian economy in the wake of Covid-19.

The tender, subject to confidentiality caveats due to the “sensitive nature of the material that will be accessed”, included a research program to examine how different countries are navigating serious skills shortages related to closed borders, vaccination requirements and other pandemic phenomena.

McKinsey was hired to do the skills-gap analysis for the “inter-departmental workforce taskforce” because the public service does not have the people or the skills required to do the job. The need they were assessing was also the hole they were filling.

It is a neat example of a problem that has beleaguered the Australian Public Service during the past decade. The longstanding imposition of a staffing cap and the changing nature of the relationship between ministerial offices and senior public servants has caused a hollowing out of skills and a huge expansion in the number and value of consulting or management advisory contracts used to plug these gaps.

In March last year, the Australian National Audit Office reported that the work outsourced to consultancies reduced in value over the years from 2009 until 2013-14, when the Coalition came to power. From there, it almost doubled to an annual $647 million five years later. When the auditor included all contracts – not just consultancies flagged within government systems – eight private firms alone received more than $1.1 billion in work agreements in 2018-19.

“Australia’s consulting industry (public and private) is the fourth largest in the world,” a new discussion paper released by The Australia Institute’s Bill Browne this week says.

“By population, Australia’s spending on consulting is greater than that of any other country, and about double that of comparable countries like Canada or Sweden.”

It is an opaque and poorly governed space, despite recent attempts to clarify precisely how these external agreements are signed, categorised and reported.

When asked for more detail about the McKinsey contract, the Department of Employment simply said: “Information on the contract awarded to McKinsey is available on AusTender.”

There is, of course, no more detail on AusTender because there is no requirement for it. This is a pattern seen over and over.

The former secretary of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C), Terry Moran, tells The Saturday Paper outsourcing is just a symptom of the larger problem.

“The reality is that the cause of that outsourcing occurring is, in my view, tied to reductions in departmental staff, contractions to Canberra and a lot of pressure – not just from politicians but from the central agencies – to use microeconomics as the Swiss Army knife of policy.”

“And it is showing. It is showing. I feel sorry for the public servants concerned – and they have got to this point largely because of a lot of change over a decade or more that has been designed to residualise the public service.”

By some counts, between 13,000 and 18,000 bureaucrat jobs have been cut from the civil service since the Coalition came to power in late 2013. As Moran notes, however, the war of attrition has not been uniform across the sector. The Reserve Bank of Australia, for example, now purportedly has the best macro-economists the government has been able to recruit in the past decade. The central agencies – PM&C, Treasury and Finance – also tend to get what they need regarding funding, but the introduction of the average staffing level cap under then minister Mathias Cormann has had a shocking effect on capability.

A former senior public servant in the Finance department told The Saturday Paper the cap was in part inspired by a fear of the impending size of the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS).

“I used to have to tell other departments, ‘Do not even ask for one extra FTE [full-time equivalent] because you will not get it. You are wasting your time,’ ” the former employee says. “But with that, the scope and scale of advice that government wanted year-on-year continued to increase and the complexity of what they wanted continued to increase and particularly at the middle level where you would get that special advice, that was being squeezed and squeezed continually.

“So, where do you get the advice? Literally, which warm body are you going to point to?”

An analysis by The Saturday Paper of contracts published on AusTender between January and October 6 this year – a period covering just over nine months – reveals that $654 million worth of management advisory services, labour hire and consulting work was granted to just six companies: Boston Consulting Group, McKinsey & Company, Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu, EY, KPMG and PwC. Deloitte alone took $212.3 million. EY won $190.7 million in contracts and KPMG $170.6 million.

None of these calculations include routine auditing or agreements for the preparation of financial statements, often completed by the big accounting firms.

As with the public service itself, the work required of these management giants is wildly variable. Deloitte, for example, was asked to complete a half-million-dollar piece of “strategic planning” regarding proposed reform of the aged-care system. About the same time, it was also signed on a $990,000 deal to “design and implement a warfare workforce” for the Navy Strategic Command. It had six months in which to do it. Later, Deloitte was paid $3.2 million to create a tool that could be used by the Future Fund to self-assess the drought resilience of potential assets in which it might wish to invest.

It has also been briefed to deliver a scoping study on possible locations for a “future regional university centre”, an integrity and governance framework for the spymasters at the Australian Signals Directorate, and work to let the navy know how it might get involved with artificial intelligence.

As a source in another Australian government told The Saturday Paper, there is a lot to be learnt just from piecing together the thousands of contracts won by firms. Take McKinsey’s work on the vaccination rollout – for better or worse – and its input into the secretive whole-of-government taskforce designed to plug yawning gaps in the Covid-normal world.

“We had Nev Power’s gas-led recovery, maybe we’ll also have McKinsey’s economic- and health-led recovery,” the bureaucrat says.

Apart from its role in supporting the maligned vaccine rollout – for a fee of $6.6 million, which quadrupled in value in six months – McKinsey was paid $2.2 million for a three-month project to advise on the business case for onshore manufacturing of mRNA vaccines, the technology that underpins the Pfizer and Moderna shots. A couple of months later, “The Firm”, as it is known to its staff, took another $2.1 million to provide advice on the “Request for Quotation” process for the same potential vaccine plant.

There is a circular logic about the sheer volume of contracts and procurement processes. Tenders are put out to manage tenders. The outsourcing is itself outsourced. In February, for example, the Department of Defence paid Deloitte $1.8 million for “contract management and procurement support”.

Two months later, as the Department of Defence continued discussions about the replacement or otherwise of the Hawk jet-fighter training system, it commissioned McKinsey to do an “affordability analysis” of the platform, which itself is owned by BAE Systems. For its efforts, McKinsey was paid $700,000 a week. BAE intends to bid for the training project to keep its Hawk system in play. Presumably that proposal will attract another round of due diligence and a further tender for consultants.

As 2017 drew to a close, the parliamentary joint committee of public accounts and audit began an inquiry into the curious world of Australian government contract reporting.

It received bipartisan support at the time, and was chaired by the Liberal senator Dean Smith. Public hearings were held on three occasions in early 2018 and more than 50 submissions were received and published by the committee.

And then it just stopped. The inquiry is officially recorded as “lapsed” and was never resumed. In a statement from the committee in April 2019, Smith simply declared: “The committee has decided not to issue a report.”

Centre for Policy Development chief executive Travers McLeod said the circumstances surrounding the buried report have not been explained.

“I think there is a mystery as to why that report was never released. I presume it was drafted,” he tells The Saturday Paper.

“At that point, both sides [of politics] said that it was a problem … and yet we have now almost had another full parliamentary term and nothing has been done. It’s not like the use of consultants has declined.”

In fact, the situation has worsened.

The late Paul Barratt, former secretary of the Department of Defence, told the parliamentary inquiry that one of the effects of increased privatisation of typical public service functions is monopolisation of advice or expertise.

“Many services are characterised by economies of scale in a way that means there will be very few capable suppliers, and one of these might over time win so much of the business that the Commonwealth agency in practice is left with little choice,” he wrote in a submission.

Barratt said a fundamental issue driving the decline of capability and core functions in the bureaucracy is the evolution of the status of departmental heads, or secretaries. This status changed materially in 1984 and again in 1999, with only minor revisions since.

“The point of all this is that over the period 1984 to 1999 we moved from a situation where there was a single point of accountability, with the requisite standing and powers, for everything that happened under the minister’s purview, to a situation in which policy formulation, implementation, service delivery, and even organisational design and organisational effectiveness, are a highly contested space,” he wrote in February 2018.

“The contemporary APS Department Secretary is a person with ambiguously defined ‘roles’ and ‘responsibilities’ under the Public Service Act, who, notwithstanding being defined as the ‘accountable authority’ under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act, is obliged to compete with a shifting population of advisers and consultancy marketers peddling their wares.”

Frank and fearless advice, as was expected from the civil servants, has been diminished ever since. The former Finance employee says watching this slide in quality was demoralising.

“When I saw the way the SES [senior executive service] level behaved, I was like, ‘Wow, you think you’re on their [the government] team,’ ” the former employee said. “And that completely skews the advice because you won’t tell them [ministers] things that they do not want to hear and you will actively try and shoehorn whatever thing that they want into whatever solution you are trying to deliver.”

Moran, who as secretary of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet wrote a review on this particular problem, titled “Ahead of the Game”, tells The Saturday Paperthat his document “tried to crystallise the role of the secretary”.

“And that was then translated into changes in the act. But it hasn’t had the effects that I had hoped it would.”

The result of this, according to others involved in the review, is that repairing the capabilities of the public service would be a decade-long effort. Now, of course, Australia is witnessing the self-reinforcing nature of the challenge. As capability declines, the use of external consultants and contractors increases. Typically, little of this outside knowledge is retained by the public service, which contributes to the cycle of depletion. Unless this changes, the public services will become more reliant on external advice over time.

Boston Consulting Group, which has been awarded $28 million worth of management or service contracts since January, happened to agree with this diagnosis in its submission to the now defunct parliamentary inquiry.

“Our view is the government should invest in growing the capability of the APS, and it should do so by ensuring that consultants are held accountable for skills and knowledge transfer to build APS capability,” it said in the submission.

“Consulting buyers should be looking to engage consultants who bring unique skills, experience and expertise that complement or enhance those available internally, not as a substitute for core functions that should be done by APS staff.”

The art of business advice – which some tried to turn into a pop science – really took off in the United States following World War II. In the 1980s, firms such as Boston Consulting and McKinsey adopted the prominent “value-based management” approach, which defined almost all organisational solutions through a single lens: maximising shareholder value. The major accounting firms, now known as the Big Four, broadened their own business base about the same time, as the market for accounting and auditing services levelled out.

Today, there is still a distinct flavour between different firms. Political masters or senior public servants often have their preferences. Sometimes it is as simple as choosing a company that they know the minister likes.

“If you had the right name on the report, the exact same thing that you would put up time and time again that would get knocked back would suddenly find more oxygen,” the former Finance Department public servant said.

“So that independent advice, in inverted commas, is the really strong rationale because the relationship with the public service in this government is completely different.”

Others who have worked directly with the top-tier consulting firms say some are better than others. By at least one informed account, Boston Consulting Group did a particularly good job of making sure stakeholder views are included in the work it does for government.

“McKinsey didn’t. And that is the main difference between the two,” the former high-level public servant tells The Saturday Paper.

Within months of the abandoned parliamentary inquiry, the David Thodey review of the Australian Public Service, commissioned by Malcolm Turnbull, was released. It sounded a dire warning about the consequences of the current advice ecosystem.

“The greatest concern has focused on the hollowing out of strategic policy skills – the ability to understand the forces at play in the world, what is needed to position the nation to meet challenges and opportunities, and to develop, analyse and provide incisive advice to the government,” it says. “This has come through in consultations, submissions and past reviews. Research undertaken for this review also states: ‘Ministers are not alone in expressing concern about the public service’s policymaking capacity ... scholars and practitioners alike have raised serious questions (and doubts) about the APS’s capacity to support policy decision-making.”

An illuminating example of this crisis is the sheer preponderance of contracts awarded in the past nine months to firms for advice, planning and implementation work regarding aged care.

This wealth of contracting happened after the release of an eight-volume final report by the Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety. Some of the recommendations will require detailed work, no doubt, but it is curious that after such a major report the Department of Health would require a $451,000 piece of work from Boston Consulting Group to “provide options and findings to enhance aged-care governance”.

After all, aged-care governance is core business for the Commonwealth.

Thodey noted in his review that caps on staffing levels in the APS have made it “difficult for agency heads to retain some functions or to maintain them at the same size and strength as previous years”.

The review says: “Some agencies reported that the caps have made it difficult to maintain long-term strategic policy functions, which has led to a divestment in analytical capability.

“While the caps have undoubtedly achieved efficiencies across the service as intended, they now risk the unintended consequence of reducing capability across the service.”

The NDIS, which was designed with about 10,000 permanent employees in mind, has less than half of that number, after a decision by then minister Mitch Fifield to devolve core functions of the scheme to a medley of non-profits and other providers.

An outcome of this has been the wildly inconsistent planning and delivery decisions touted as the reason to introduce the now abandoned independent assessments.

Nevertheless, new contact information reported by the scheme agency shows it still paid almost $3 million to two companies running the doomed pilots in the past financial year.

The National Disability Insurance Agency also spent $190 million on labour hire, temporary personnel or “recruitment support”; a further $97 million to its outsourced delivery partners; and $30 million on the privatised call centre run by Serco.

According to The Australia Institute, that kind of cash could hire about 3000 public servants. The $1.1 billion spent on the top-tier contracts in 2018-19 “could instead employ an additional 12,000 public servants, which would allow the skills and knowledge to be brought within the public service”.

In the case of the NDIS, the festival of outsourcing has created a bolt-on system of employees, planners, early intervention providers and co-ordinators operating completely out-of-synch with the central agency. Even the second most powerful person at the NDIA, scheme actuary Sarah Johnson, a PwC alumna, is and has always been a contractor.

Sometimes, however, the clearest way of communicating the gutting of the public service in Australia is to use its own words.

In May, the Department of Defence awarded a $178,000 contract to KPMG for a fairly straightforward mission: to develop a strategic narrative for the armed forces.

The reason this consultancy was awarded in the first place? “Skills currently unavailable within the agency.”

This article was first published in the print edition of The Saturday Paper on Oct 9, 2021 as "How private management consultants took over the public service".

A free press is one you pay for. In the short term, the economic fallout from coronavirus has taken about a year third of our revenue. We will survive this crisis, but we need the support of readers. Now is the time to subscribe.