Paul Bangay is even known at Vallauris a town noted for ceramics, glass, the bitter orange tree... and Picasso - it is part of the Ventimiglia region

The Loss of Dark Skies Is So Painful, Astronomers Coined a New Term For It: ‘Noctalgia‘ Space

Why Australia’s top garden designer is embracing natives

How Paul Bangay, Australia’s most celebrated garden creator, went from sustainability to ostentation and back again.

Paul Bangay is looking at a bare patch of dirt in the vegetable garden at Stonefields, the 20-hectare property in Victoria’s central highlands he bought in 2004 and turned into one of the country’s most significant and admired gardens.

If you look close enough you can see green shoots,” he says. It’s midwinter, and Bangay is wearing brown chinos and a chambray shirt under a puffer jacket.

Paul Bangay at Stonefields Brendan McCarthy

The asparagus just beginning this season’s journey to the sun is a two-decade old perennial. Bangay got from a 140-year-old farm, making it potentially older still. Genetically it’s thousands of years old – a wild species first cultivated by the Romans.

Bangay shifts his attention to stands of bare, truncated sticks that will soon transform into sumptuous dark red roses. Being able to see into the future is a key trait for a landscape designer, especially one who intends his work to be around long after he’s gone.

He particularly admires long-lived gardeners like Dame Elisabeth Murdoch, who spent 80 years tending her gardens at Cruden Farm (of which he is a trustee), one hour south of Melbourne. “She is the only person I know who planted an oak and lived to see it grow to maturity,” he says with something approaching awe in his voice.

Stonefields.

Accompanying him on his rounds is Ruby the caramel-coloured cocker spaniel and Harold the peacock, who jumps up on a table and promptly defecates all over it. “Mind the poo,” he says with equanimity.

Bangay is waiting for settlement on Stonefields, which he sold for $11 million in January to a resort consortium fronted by celebrity gardener Jamie Durie. His husband, Barry, a gentle-voiced Irishman whom he married in 2014, spends most of his time here while Bangay splits his week between Sydney and Melbourne, meeting clients and working with his nine staff. His studio designs between 70 and 80 gardens a year.

As well as leaving Stonefields, he has a book coming out, his tenth. Paul Bangay: A Life In Garden Design is filled with photos and detailed plans of gardens he has designed over 30 years, along with personal pics going back to his childhood. It documents how an Australian style of gardening evolved, and records a social world now disappearing.

“It’s not an autobiography,” he insists, adding with a chortle “… that would be X-rated.”

The young Paul planted his first garden at age six, and dreamt of a small acreage where he could keep goats and chickens. He thoroughly subscribed to the native plant movement of the 1970s that his parents joined. His childhood garden in the foothills of the Dandenong ranges consciously mimicked the surrounding bush, with casuarina trees, grevillea and hakeas for the birds.

Paul Bangay, the young organic farmer, from The Age, 30 September, 1980. Fairfax Archives

His parents never had a problem with him being gay, he says, but his transformation into the go-to guy for classical European-style gardens – the “darling of the mink and manure set” as Vogueonce called him – still perplexes his mother.

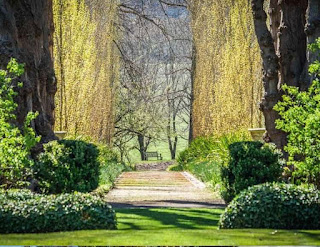

The formal entry to Stonefields, with peacock. Simon Griffiths

Bangay walks between the high glossy hedges that form the entry to Stonefields, along paved paths that take the visitor through a series of ″rooms″, with glimpses of wisteria terraces, mossy trails, and giant gums with hellebores and topiary balls at their base, spied through circular portals and blue-framed doorways. Monumental urns contribute to the sense of scale and proportion.

The house resembles an Italian villa and overlooks a deep valley. Pointing towards the view is a rectangular pond (green, his “go-to colour” for pools) flanked by identical rows of precision-cut buxus half-cubes, like square buttons, that march towards the horizon.

“People think a formal garden is a lot of work, but it’s the opposite,” he says. “Those hedges are clipped once a year, so they take just a few hours to maintain compared to weeks if it was all flowers.”

Out here in the shadow of the Macedon ranges, rural hedges have a practical role: they act as breaks from the winds that sweep down the hills and over the paddocks, providing protection and privacy.

Formal gardens are static, meaning they stay the same throughout the seasons – an advantage for Australians who want to enjoy the outdoors all year round.

Bangay clearly adores tradition and has a profound knowledge of garden history.

A wide stone terrace that descends gradually to the front door was inspired by a visit to Islamic “paradise gardens” in Iran. A channel of running water (known as a “rill”) divides the terrace centrally, studded by square pools of iris and coils of bronze snakes sculpted by Ivana Perkins.

Bangay’s living room is the lair of a serious bibliophile: a place of deep sofas and dark-wood surfaces, monumental limestone fireplace ablaze, and stacks of magazines on the plush ottoman. One of the bookcases swings open to reveal the main bedroom and four-poster bed.

The living room at Stonefields with its door to the bedroom hidden behind a bookcase.

Even before he finished his course at Burnley Horticultural College in Richmond, Bangay had designed his first large-scale garden: Larundel, the 19th-century sheep station near Ballarat owned at the time by the Kimberley family.

Although he can’t quite remember, he thinks he was introduced by society florist Kevin O’Neill, whose shop he worked in. O’Neill not only introduced him to his first wealthy clients, but also backed Bangay’s first business in Toorak Road in Melbourne.

Another mentor and friend was the interior designer John Coote, whom he calls “the last grand decorator”, known for his chauffeur-driven Daimler flying the Victorian flag.

Despite being “all Western Districts”, Coote became the lord of an 18th-century Palladian mansion in Ireland and opened offices in New York and London. He introduced Bangay to English aristocracy, including designer David Hicks, at that time married to Lady Pamela Mountbatten.

John Coote with Robert Doble, Paul Bangay and an Irish wolfhound at Coote’s Irish estate, Bellamont Forest, which Bangay describes as like being in a Cecil Beaton painting. Rene Kramers

Hicks encouraged Bangay in his love of British and Continental garden traditions, but also encouraged him to move on from pastiche towards a style of his own, one that echoed Australian Edna Walling’s style with its romantic mix of stone walls, swaths of bulbs and a smattering of natives.

Bangay describes The Grove, David Hicks’ house in England, in a phrase that could easily be ascribed to his own work: “masculine, architectural, green, simple and individual”. A more relaxed and confident Bangay had arrived.

In 1998, he spoke at Hicks’ funeral. Afterwards, he was sat next to a handsome older Greek man. When he proudly asserted that Melbourne was the second-biggest Greek city in the world, the unknown guest disagreed, and they hotly debated who was right.

“Who was that man?” he asked Hicks’ daughter, India, with some exasperation. “King Constantine of Greece,” he was told.

To a certain extent, Bangay is beholden to what his clients want. That might mean explaining why hydrangeas and banana trees don’t grow together, or arguing with someone who wants him to remove a fully grown maple “because it is bare in winter”.

Paul Bangay at work in the mid-1990s.

He has designed inner-city courtyards and single-colour gardens. While he admires Japanese gardens, and thinks they would grow well in southern states, he has yet to install one. “No one has ever asked me,” he says.

The Mediterranean gardens he loves are still a great benchmark for Australia, he believes, but we have grown up and developed a style of our own in which natives will become increasingly dominant.

The lavish rose gardens and grassy expanses of his early style are increasingly difficult to do. Water sourcing can no longer to be taken for granted, and heat-sensitive species like rhododendrons won’t grow in the suburbs any more. Drought is expected.

“Everyone knows it’s coming,” he says.

Nowadays, he restricts the size of ornamental garden beds to save on water. While he still likes the sculptural quality of clipped buxus, he is looking at using native westringia (coastal rosemary) instead, softened by ornamental grasses and hardy perennials.

“Lawn requires the most maintenance of anything in a garden,” he says. If a client can’t let go of lawn, he would suggest gravel, which is permanent and permeable.

Mature style: softer, more relaxed planting schemes of Agastache ’Sweet lili” and Verbena bonariensis. Simon Griffiths

When Bangay was growing up in the 1970s, natives couldn’t be found in nurseries. That is changing, but he frowns on people who pillage tree ferns and other species from the bush. And as for developers who denude a block to build a house, they should be fined – $200,000 for a 200-year-old tree, he reckons.

Back at Stonefields, the garden is dissolving into shadow. Garden lights are good in the city, he says, but a no-no in the country. The darkness and the quiet are what it’s all about. He prefers country clients as well: he likes spending a few days getting a brief rather than an hour in the city.

“I want to make fewer gardens, but bigger ones,” he says, dispelling any thought that he is about to retire. His next home will have trees – slow-growing oaks and blackwood wattles. Hedges, maybe, but in more whimsical or organic shapes.

His only must-have, he says, is a walled vegetable garden, safe from the predations of wallabies, deer … and Harold the peacock.