The older I get the more I realise that all of the cliches are true. Honesty really is the best policy. And it is often a greater compliment to be trusted than to be loved

Dear ATO, the London shows went really well. They were a great way to finish the financial year. After this photo, we all completed our BAS forms. Love TG.

Tom Gleeson and his travelling deductions

Trust Kathy Lette to cover Putin and other current affairs in style and not just women at the ATO Using humour much more than a journalist and better than any Senior Executive Amen 🙏

Tucked into the pages of the novel is a card signed by the author. Tokarczuk said in her Nobel lecture:

“Fiction has lost the readers’ trust since lying has become a dangerous weapon of mass destruction, even if it is still a primitive tool. I am often asked this incredulous question: ‘Is this thing you wrote really true?’ And every time I feel this question bodes the end of literature.”

The Scarcest Thing in the World

It's not oil or eggs or toilet paper—but something far more important

Here are some news stories from recent days. Can you tell me what they have in common?

Scammers clone a teenage girl’s voice with AI—then use it to call her mother and demand a $1 million ransom.

Millions of people see a photo of Pope Francis wearing a goofy white Balenciaga puffer jacket, and think it’s real. But after the image goes viral, news media report that it was created by a construction worker in Chicago with deepfake technology.

Twitter changes requirements for verification checks. What was once a sign that you could trust somebody’s identity gets turned into a status symbol, sold to anybody willing to pay for it. Within hours, the platform is flooded with bogus checked accounts.

Officials go on TV and tell people they can trust the banking system—but depositors don’t believe them. High profile bank failures from Silicon Valley to Switzerland have them spooked. Over the course of just a few days, depositors move $100 billion from their accounts.

ChatGPT falsely accuses a professor of sexual harassment—and cites an article that doesn’t exist as its source. Adding to the fiasco, AI claims the abuse happened on a trip to Alaska, but the professor has never traveled to that state with students.

The Department of Justice launches an investigation into China’s use of TikTok to spy on users. Another popular Chinese app allegedly can bypass users’ security to “monitor activities on other apps, check notifications, read private messages and change settings.”

The FBI tells travelers to avoid public phone charging stations at airports, hotels and other locations. “Bad actors have figured out ways to use public USB ports to introduce malware and monitoring software onto devices,” they warn.

The missing ingredient in each of these stories is trust.

Everybody is trying to kill it—criminals, technocrats, politicians, you name it. Not long ago, Disney was the only company selling a Fantasyland, but now that’s the ambition of every tech empire.

The trust crisis could hardly be more intense.

But it’s hidden from view because there’s so much information out there. We are living in a culture of abundance, especially in the digital world. So it’s hard to believe than anything in the information economy is scarce.

Whatever you want, you can get—and usually for free. You can have free news, free music, free videos, free everything. But you get what you pay for, as the saying goes. And it was never truer than right now—when all this free stuff is starting to collapse in a fog of fakery and phoniness.

Tell me what source you trust, and I’ll tell you why you’re a fool. As B.B. King once said: “Nobody loves me but my mother—and she could be jivin' too.”

Years ago, technology made things moretrustworthy. You could believe something because it was validated by photos, videos, recordings, databases and other trusted sources of information.

Seeing was believing—but not anymore. Until very recently, if you doubted something, you could look it up in an encyclopedia or other book. But even these get changed retroactively nowadays.

For example, people who consult Wikipedia to understand the economy might be surprised to learn that the platform’s write-up on “recession” kept changing in recent months—as political operatives and spinmeisters fought over the very meaning of the word. It got so bad that the site was forced to block edits on the entry.

There’s an ominous recurring theme here: The very technologies we use to determine what’s trustworthy are the ones most under attack.

Tell me what source you trust, and I’ll tell you why you’re a fool. As B.B. King once said: “Nobody loves me but my mother—and she could be jivin' too.”

If you want answers, you go to Google—but it’s now crammed to the brim with paid placement ads. Or nowadays you ask AI, but that tech has turned into a joke due to plagiarism, fake sources, and clumsy errors. Or you ask an expert—but even the word expert is now used with contempt.

As I’ve written elsewhere, all experts are now mocked and attacked. It’s not just journalists or college professors. Every kind of expertise has taken a hit.

At first, politicians took the biggest hit. During the course of my lifetime, public trust in elected officials has collapsed from 75% to 25%. There’s plenty of finger pointing, but the decline continues no matter which party is in power.

No expert is exempt from this distrust. Consider the case of scientists—who now struggle with a replicability crisis that casts doubt on even the most respected peer-reviewed studies. But it’s just as bad with medical experts, pilloried and denounced throughout the COVID pandemic.

Tracking polls reveal how widespread the trust erosion really is. And it accelerated during the pandemic.

Trust is the scarcest commodity in the world. Nothing else comes close.

It has reached crisis proportions, and is getting worse. Compared to the trust deficit, all other shortages—eggs, toilet paper, vinyl albums—look modest in contrast.

The speed of this erosion is scary. You can almost measure it week by week.

Just a year ago, if I had told you that AI was in love with a NY Times reporter and trying to break up his marriage, you would have thought I was describing a sci-fi screenplay. But it’s now just another tech news story.

Or if I had told you that your dinner at a Paris restaurant might be made out of bugs, you would have thought this was a horror film or comedy routine. But not anymore—so take a close look at that special du jour before chowing down.

In a simpler day, crypto execs didn’t have their hologram conterfeited to scam money over a Zoom call. But hey, that’s how things roll in 2023.

And what would you think if, just a few months back, I’d asked you to pick out a code word that you could use to prove your were a human being when dealing with family and loved ones? That sounds like something out of the paranoid mind of Philip K. Dick. Or at least it did until the current moment, when it’s actually good advice.

How did we get here?

It’s hard to figure out who is the worst culprit in our trust crisis. Mark Zuckerberg, for example, wants you to leave reality entirely behind, and participate in a fake metaverse where everything is a construct. But all the other tech empires—Microsoft, Google, etc.—have their own investments in trust-destroying innovation.

Trust-based communities aren’t some impossible dream. They existed long before the digital age. And they could exist today too.

Of course, some are fighting against this. They are trying to restore trust—with encryption or blockchain or some other cure-all. But I fear that those rebels are losing the battle. Just consider all the failed attempts to create AI-detection software—which is sadly unreliable and may only further erode trust.

It doesn’t have to be this way.

Mark Zuckerberg bet his entire company on something fake—but he could just as easily have tried to increase the trustworthiness of his platform. Users would have loved that, and embraced it with much more enthusiaism than his failing metaverse.

Google could have improved the reliability of its search results—but decided to maximize short term profits by diluting their value.

Microsoft responded by turning its rival search engine Bing into the poster child for untrustworthy AI data, but could have done the exact opposite.

Twitter could have strengthened its validation process rather than sell it as a status symbol.

The CEOs at these companies clearly don’t understand how much people crave trustworthy sources in the current moment. If they would focus their investments on enhancing trust, they would actually make more money in the long run.

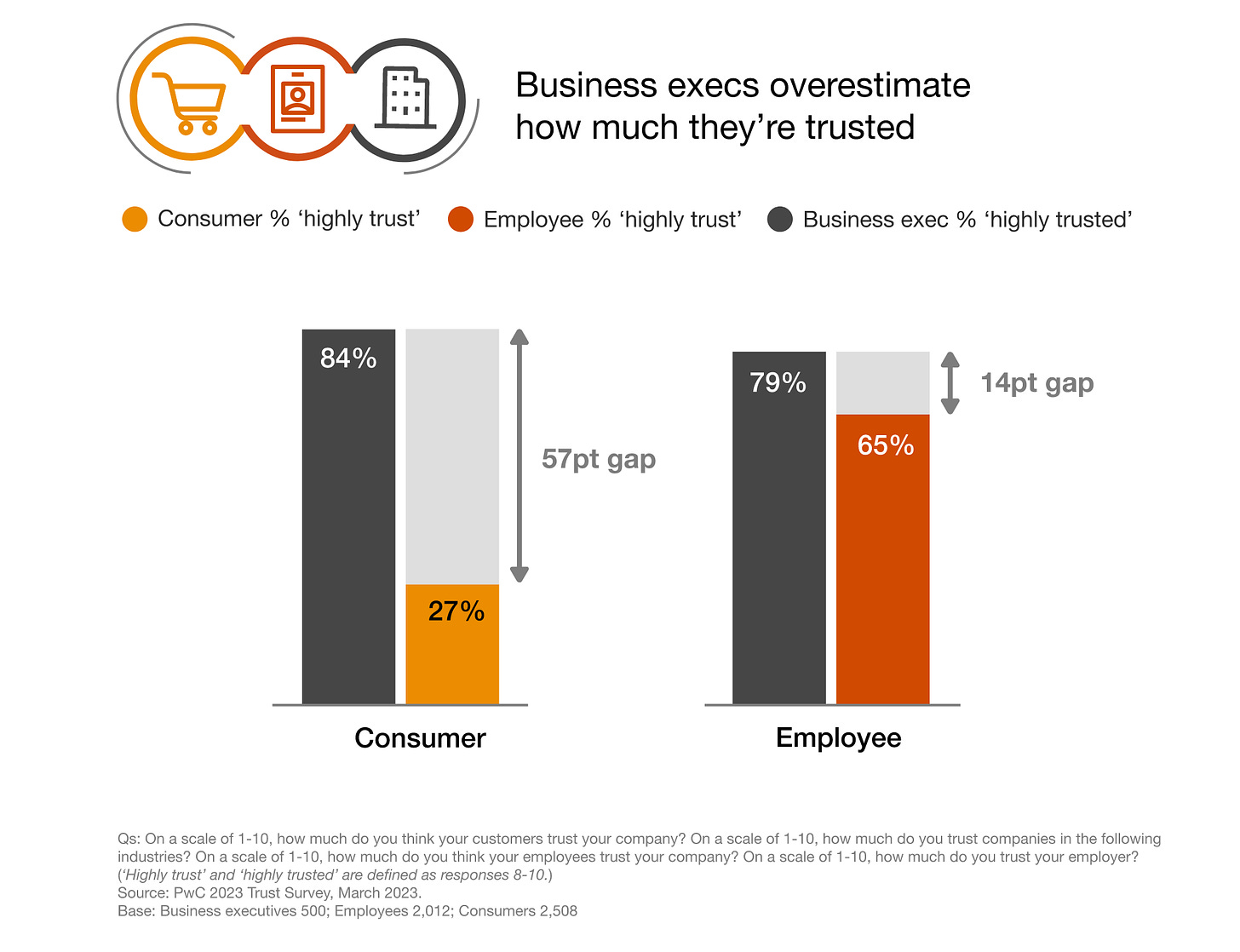

A recent survey showed that business execs overestimate how much they’re trusted—and by a huge gap of 57 percent!

I’d pay more for trust, and I’m not the only one. The worse the trust crisis gets, the more others will join me.

If you’re not on board yet, just wait until you have to deal with identity fraud (which happened to me). Or have your social media account hijacked (which also happened to me). Or have a dude in Vietnam use your bio for some indefinable reason (that too).

The tech titans haven’t figured this out yet, but they are building a huge market opportunity—only for someone else, more honest and reliable than themselves.

Trust-based communities aren’t some impossible dream. They existed long before the digital age. You might even say that they provided the basis for human societies. And they could exist today too—both online and in the real world.

It’s no secret how you construct one. You emphasize transparency and straight talk. You don’t manipulate people—which is the defining vice of our age. Instead you respect their rights, which also come with responsibilities. Above all, you strive for honesty.

There’s a reason why I call this newsletter The Honest Broker. We’ve reached a point where that’s a more powerful pitch than “Smart Broker” or “Handsome Broker” or “Rich Broker.”

How hard is it to speak forthrightly and frankly? You would think that’s an easy thing to achieve. And maybe it was in the past, but not in the current moment.

The people running these huge techno-monopolies could learn a lot by talking to the rest of us. The technocrats taught us not to trust what we find on the web. Now we need to teach them why this matters.