Drug cheats or gold medallists? The ATO’s war with the miners

The Tax Office says the big companies skirt the rules – the industry body says they are star a contributor of public funds. Rio’s $991 million settlement could be just the start.

A “handy amount”. That’s how Anthony Albanese described the almost $1 billion in extra revenue added to the badly stretched federal budget from a landmark settlement with miner Rio Tinto last week.

One of the biggest settlements in the nation’s tax history, the $991 million deal related to Rio’s long controversial Singapore marketing hub and a tax deduction claim associated with financing a company dividend. It could be the first in a series of major settlements with big multinationals coming in the months ahead.

ATO Commissioner Chris Jordan says the hard work has been done to get the big mining companies paying their fair share. Andrew Meares

Eager to extract more money from multinationals engaging in tax avoidance, the prime minister was happy for the Australian Taxation Office to take a victory lap following the announcement. He said the opportunity cost from unpaid tax went directly to unfunded hospital beds, university places and infrastructure around the country.

Worse still, ordinary taxpayers working nine to five every day and paying their fair share of tax were “being ripped off”.

Both Albanese and ATO Commissioner Chris Jordan have hinted more high-profile settlements could be pending.

In a rare interview, Jordan told The Australian Financial Review that resources companies dodging their tax obligations were like drug cheats at the Olympic Games.

After years of hard work, the resources sector has started paying tax, he declared.

“Audit yield is no longer the paradigm. There’s no point settling with these companies and then having to do it all over again.”

Revenue yield from audits is the additional corporate tax liability uncovered from compliance activities by the ATO, and is the result of expensive and often lengthy investigations.

Rio’s settlement related to a disagreement about interest on borrowings used to pay an intra-group dividend in 2015, as well as the pricing of transactions between Rio entities in Australia and the Singapore “commercial centre” from 2010 to 2021.

The use of such commercial hubs has been controversial, raising questions about why pricing of commodities within the same company would be marked up between Australia and Singapore.

Rio says the hub undertakes sophisticated shipping procurement and marketing activities for the company’s global business.

Moving the needle on big corporates

UNSW taxation expert Professor Bob Deutsch said the announcement showed Australia was making real progress on corporate tax minimisation.

“I think they are, in the context of multinationals, being brought into line on questions of transfer pricing and marketing hubs,” he told The Financial Review.

“They’re obviously going to have to generally be more realistic about the pricing that they charge within the group on products that they transfer between companies in different jurisdictions, which really is what transfer pricing is all about, ultimately.”

Deutsch said Rio, BHP and the landmark Chevron case were moving the needle on tax performance for big corporates.

At least $10 billion in extra tax revenue was locked in after Chevron, the oil and gas giant, abandoned a High Court challenge in its major transfer pricing dispute with the ATO in August 2017.

“I think they’re signals to companies generally that they’re going to have to be more careful about the pricing, and to charge things on a more consistent, arm’s length basis,” he said.

“I think that message is slowly starting to permeate the sort of upper echelons of the corporate world in Australia. It has taken a long time, but certainly the activities of the ATO in the last 15 years has started to sort of bear fruit and I think it will continue.”

Deutsch said smaller companies would change their behaviour as well, describing Australia as being at the vanguard of international trends, rather than behind the eight ball.

“I think that the Australian revenue authorities have been perhaps more vigorous in this area than some of their counterparts in other jurisdictions.

“I think we’re doing a pretty good job in terms of getting to the root of the problem, and getting companies to fall in line with what more realistic pricing arrangements.”

Miners hit back

But Jordan’s drug cheat comparisons angered the big miners.

Minerals Council of Australia chief executive Tania Constable expressed disappointment at his tone, pointing out that the firms were among Australia’s biggest taxpayers and in many cases miners had alerted the ATO to their own problems.

Rather than drug cheats, the MCA said the sector was actually an “Olympic gold medallist” at contributing to public revenue.

“The commissioner implies that if not for ATO audit activity, tax settlements reached with Rio Tinto and BHP would not have occurred. This is incorrect,” Constable said in a statement.

“The matters settled in those cases were raised by the taxpayers with the ATO in the normal course of flagging issues where the tax treatment is not clear-cut. In the case of the issues settled with Rio Tinto, the marketing hub matters were first raised by them with the ATO in 2005.”

BHP and Rio Tinto paid more than $10 billion in company tax in the 2019-20 tax year. The ATO’s own corporate tax transparency data showed the resources industry contributed more than 40 per cent of all the company tax reported by the 2370 biggest taxpayers.

“Australian mining can be relied upon to pay its fair share of tax and royalties to pay for schools, hospitals and other infrastructure,” Constable said.

Separate to the Rio deal, hundreds of businesses using offshore tax havens and complex corporate structures are on notice to reorganise their affairs before July 2023, as Labor plans to target the “scourge” of multinational tax avoidance.

A trend emerges

The government plans to raise nearly $1.9 billion from boosted transparency measures and Tax Office reporting requirements, including stopping firms with links to offshore locations such as the Cayman Islands and Bermuda from winning government contracts.

One longtime tax watcher said a trend was emerging. Asking not to be named because of corporate sensitives, they said the government’s anti-tax avoidance taskforce and public announcements of major settlements highlighted Australia’s less litigious culture in tax disputes.

The ATO would welcome more announcements of high-profile settlements as a signal to other corporate taxpayers doing the wrong thing and potentially avoiding lengthy court actions, the expert suggested.

This week, American oil giant ExxonMobil said it was trying to resolve the ATO’s concerns about the interest rates it charged on loans to its Australian subsidiaries.

The ATO has raised concerns with the interest rates that foreign subsidiaries of Exxon charged on loans to Exxon’s Australian subsidiaries and how those interest charges affected the company’s 2010 and 2011 accounts.

The same issue is expected to affect Exxon’s Australian tax payments in the subsequent 10 years, and bears a striking resemblance to the model used by Chevron in 2003.

For his part, Anthony Albanese is holding firm against tax avoidance by corporate giants. He said authorities including the ATO would not take a backwards step.

“The Tax Office will be doing their job,” the prime minister said. “We will be providing them with all the resources they need.”

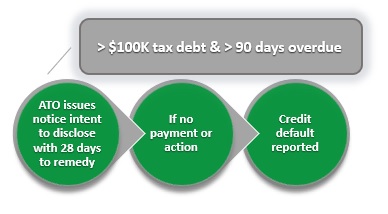

You may have heard about the ATO's new policy to disclose non-compliant businesses with tax debts greater than $100,000 to Credit Reporting Bureaus. This is another tool available to the ATO to encourage taxpayers to manage and pay outstanding debts.

Recent market volatility, interest rate hikes, inflation, and ballooning tax debts through Covid, makes this a timely reminder for business and their advisors.

The ATO resumed debt collection activity in 2022, following a lengthy hiatus. The ATO has begun issuing warning letters, Director Penalty Notices and, recently, winding up applications. In negotiating payment arrangements with small to mid-sized taxpayers, the ATO are seeking mortgages over real property or bank guarantees as security, which is becoming challenging for business owners in a softening property market, with tightening credit.

To date, the ATO has been sparing in terms of disclosing tax debts to Credit Reporting Bureaus. However, the broader need for the government to engage in "budget repair" may prompt the ATO to take a harder stance when it comes to recovering tax debts from non-compliant taxpayers.

The risk to the business is obviously through their credit rating, where the public disclosure of defaults can impact their supply and financing facilities. Tax compliance and the management of tax debts are an important part of the credit assessment process. Public reporting of tax defaults brings this matter up front.

The key message for business owners is to engage with the ATO when tax debts escalate, either directly or through their trusted advisors. However, if the tax debts cannot be paid now, or over time by agreement with the ATO, then there are other options available to address operational and balance sheet issues as a whole. At BRI Ferrier, we are regularly engaged by businesses to explore restructuring solutions through formal processes such as:

- Safe Harbour advisory

- Small Business Restructuring

- Voluntary Administrations

- Liquidations

Below is a high-level summary guide to the ATO's tax debt disclosure policy:

Applies to:

|

Process:

|

Remedy:

|

More information can be found on the ATO's website https://www.ato.gov.au/General/Paying-the-ATO/If-you-don-t-pay/Disclosure-of-business-tax-debts/