A few months ago, I promised some nice people in New York that I would, sometime very soon, write a book.

Since then, I have:

Called my mom rejoicing.

Called my mom crying.

Considered changing my Twitter bio, then thought better of it.

Considered emailing all my ex-boyfriends and mentors to let them know I’m an impostor, then thought better of it.

Extensively researched three different long-form writing softwares, only to find that I prefer the first one I ever tried.

Researched and bought several different types of special German pens, only to find that I prefer good old Paper Mates.

Now just one task remains: Write the thing.

To that end, I recently consulted with some productivity experts to figure out how it is that people—such as, hopefully, myself—are able to accomplish big, long-term projects, within the time allotted, and ideally with minimal psychiatric help.

I reached out to Laura Vanderkam, who has written several books, most of them about the art of getting things done. (She sees your Lean In and raises you I Know How She Does It: How Successful Women Make the Most of Their Time.) She has a book come out every 18 months to two years, but most of the writing gets done in six months, she told me. After that, she’s editing and promoting the book. And between everything, she’s blogging, podcasting, speaking, and traveling. Oh, and she has four children, ages 11, 8, 6, and 3.

How to write a book about Cold War RiverFor 1,500 years, Western Europe

‘forgot’ how to swim, retreating

from the water in Terror.

The return to swimming

is a lesser-known triumph of the

E n l i g h t e n m e n t.

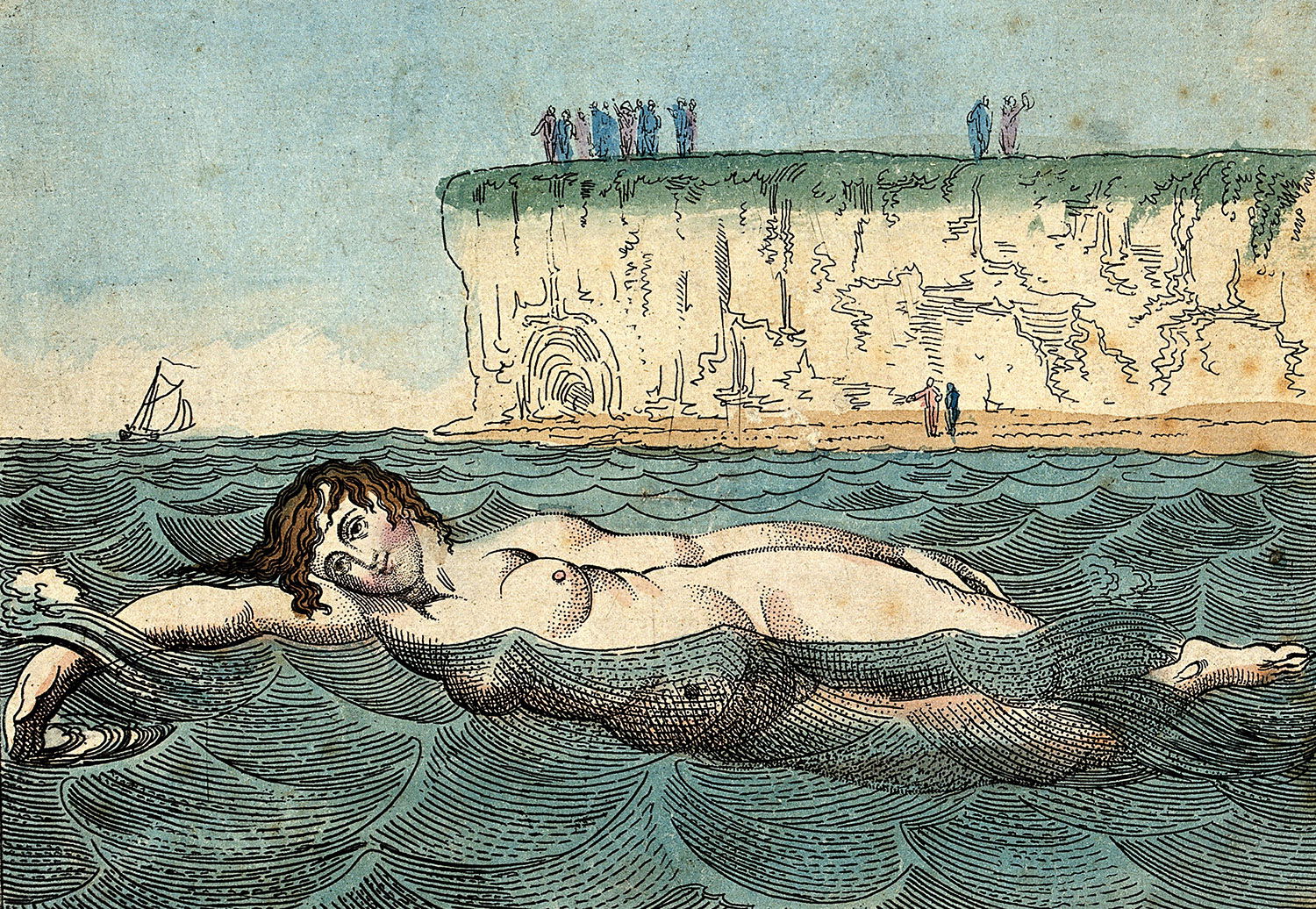

A woman swimming in the sea in Margate, Kent, Thomas Rowlandson, c.1800

Humans first learned to swim in prehistory – though how far back remains a matter of debate between the paleoanthropological establishment and the followers of Elaine Morgan (1920-2013), who championed the aquatic ape hypothesis, an aquatic phase during hominid evolution between 7 and 4.3 million years ago. Even though we may never have had an aquatic ancestor, compelling evidence exists for the swimming abilities of the representatives of the genus Homosince H. erectus, who appeared some 1.8 million years ago. In the historical period, the myths of the ancient civilisations of the eastern Mediterranean testify to a positive relationship with water and swimming, mediated until late antiquity by a pantheon of aquatic gods, nymphs and tritons.

By the medieval period, the majority of Western Europeans who were not involved in harvesting aquatic resources had forgotten how to swim. Swimming itself was not forgotten – but the ability to do so hugely decreased. Bodies of water became sinister ‘otherworlds’ populated by mermaids and sea monsters. How do we explain the loss of so important a skill? Humans have never given up running, jumping or climbing, so why did so many abandon an activity that was useful to obtain food and natural resources, vital to avoid drowning and pleasurable to cool down on a hot summer’s day?