Many current and former PwC partners still don’t believe the tax leaks scandals involved any serious wrongdoing, and regulators can’t be sure there will not be a repeat.

Edmund TadrosProfessional services editor

Almost 18 months after the tax leaks matter first broke, PwC Australia is still unable to break free of the scandal. The reason is cultural. Despite the apologies, the promises of change, and the introduction of onerous new processes, rules and oversight, the firm’s operatives will, by its very nature as a sales-driven partnership, continue to struggle to balance purpose and profit.

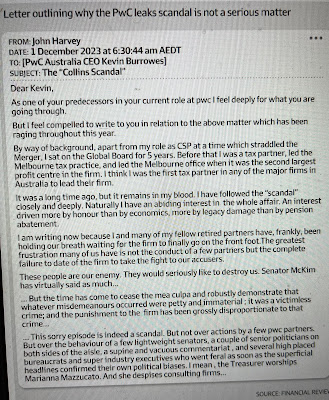

There are multiple signs of this struggle. Many current and former PwC partners challenge the idea that the tax leaks matter involved any serious wrongdoing. They still argue – despite multiple reports saying the opposite – the scandal was nothing more than the sharing of almost trivial information about impending tax laws that were widely flagged by the government. A “victimless crime” hyped up by “the enemy”, in the words of one former leader.

Then there is the fact that PwC Australia CEO Kevin Burrowes, the overseas senior partner parachuted in by PwC International to fix up the local firm, faces conflict of interest claims over the belated revelation he is being paid by both the Australian and global firms. Former CEO Luke Sayer told parliament that “Australian partners [would] perceive there to be a conflict. Are you working for our interests or global’s interests?”

There is also PwC International itself, the London-based company that runs the PwC brand and sets and polices the member firms in its global network. Its refusal to release the report by law firm Linklaters into the actions of overseas partners involved in leaks matter has led Australian parliamentarians to accuse the firm of running an ongoing cover-up over the scandal. The international firm cited legal professional privilege as the reason it has only released a summary of the report.

A follow-up report by former Australian Tax Office second commissioner Bruce Quigley into the PwC tax and legal division at the heart of the scandal found that there had been little change. There was, he wrote, “a degree of scepticism” from ATO officials that the firm would be able to put its “values before growth and profit”.

The report, completed last month, also found tax officials are still waiting for the purported change in the firm’s attitude “to be demonstrated ‘on the ground’.”

That report also highlights the continued self-pity, and focus on sales, that drives PwC personnel. Many partners and staff within the area where tax and legal sit “feel hurt and stressed” over the leaks matter, leading to the loss of “a lot of talent and experience in a short space of time”, while the “extremely negative impact on the PwC Brand” had made “it difficult to attract new clients”.

But they are still making sales. “Whilst there was confidence that most existing clients will stay with the firm, some have been lost and there were some reports of other clients questioning their ongoing relationship and being more selective in the work that they will engage PwC on in future,” Quigley wrote. “Nevertheless, there was a degree of optimism going forward.”

Tax and legal, which has been elevated to its own division within the firm, was a standout performer in the last financial year.

The consequences of the leaks scandal have been far-reaching, and are far from over

Laws around tax advisers have been significantly tightened. The Labor government has pushed through new rules to impose penalties of up to $780 million for tax promoter breaches, new promoter penalties, changes to Tax Office secrecy and wider powers for the Tax Practitioners Board, in what it described as the biggest crackdown on tax advisers in Australian history.

Treasury is now consulting on a range of related matters, including whether the TPB’s sanction regime should be toughened; if the ATO should be given additional investigation and information-gathering powers; and how the big four are structured and regulated.

Labor has also used the PwC tax leaks scandal to fulfil a campaign promise to cut back the use of external advisers and contractors by the Commonwealth and to beef up the public service. At the same time, Finance has dramatically tightened the rules around how consultants and contractors are used by the bureaucracy. The government had cut the money spent on the largest consulting firms by nearly 50 per cent, to more than $600 million, in FY24.

This has hit the major consulting firms hard, particularly as it coincides with reduced demand for their services generally thanks to anaemic economic growth. It has led to widespread cost-cutting and job losses at PwC and its big four rivals Deloitte, EY and KPMG.

PwC Australia has suffered the most – it is now a third smaller than last year – but is also the most changed of the big four. The company lost the marquee Westpac external audit (worth about $35 million in annual fees), and Lendlease changed its mind about awarding its external audit to the firm ($9 million). It did, however, retain the Macquarie Group audit ($66 million in fees).

The careers of hundreds of partners and potentially thousands of staff have been derailed by the scandal. Being a part of PwC used to open doors. Now it’s a slightly embarrassing admission that must be explained.

Many threats remain. There are multiple ongoing probes into the matter, including by the Australian Federal Police (an investigation named Operation Alesia that has gone international), the TPB (nine investigations) and professional body Chartered Accountants ANZ (multiple investigations).

There is also the ongoing joint inquiry, chaired by Senator Deborah O’Neill, into the structure of the big four consulting firms.

The now-finished Senate consulting inquiry, chaired by Liberal Senator Richard Colbeck, reported in June after two earlier scathing reports dedicated to the PwC leaks matter.

The inquiry’s final report on the scandal, released in mid-June, again demanded that the firm come clean about who was specifically involved in the matter in Australia and overseas.

Colbeck began the hearings with a neutral air but became increasingly infuriated with the inability of PwC to respond directly to questions. “If they think this is going away, they’re living in cloud cuckoo land,” he says. “We’ve got [Senate] estimates, we’re back again in November. This is not just a local story. It’s bigger than that, and there’s still some work to do there in that.”

The firm’s CEO, Burrowes, has pushed through changes to the firm’s governance and partnership model designed to prevent a repeat of the tax leaks matter. These include new independent directors and an independent chairman in the firm’s governance board.

These changes go some way towards addressing specific problems within the firm’s pre-leaks governance structure. But a fundamental problem remains. It is that the culture remains profit- and sales-driven, and rules remain mostly unenforceable by outside regulatory bodies.

This means the cycle of scandal, apology and promises of internal reform could continue.

As for the key former players, some are moving on, while others are stuck in limbo.

Sayers says privately that the negative publicity around the leaks matter has cost his business tens of millions in potential earnings. He remains bewildered as why he has been so aggressively targeted by politicians.

Sayers, who left the firm in 2020 and formed an eponymous advisory and investment firm, Sayers Group, feels deeply betrayed by PwC Australia and PwC International. He has told friends he has gone out of his way to take responsibility and to not reveal who he thinks is to blame for creating the firestorm (a list that heavily features PwC International figures).

For example, he feels that by not naming specific names, the Ziggy Switkowski report skirted who was actually responsible for the firm’s troubled governance structure.

Another irritation was the move by Burrowes to blame Sayers and Seymour at a Senate committee hearing last October and last week.

The four partners initially named by PwC Australia as having received the tax leaks emails and who had their post-retirement payments stripped – Peter Collins, Neil Fuller, Paul McNab and Michael Bersten – have fared differently. Collins has never spoken publicly about the matter. Fuller later sued the firm and the matter settled out of court on unknown terms.

Bersten and McNab are both furious with PwC for naming them and have denied any wrongdoing. They point out that the firm itself stated that the four partners had left the firm for “reasons unrelated to the involvement” in the tax leaks matter.

McNab, who felt he had to resign from a role at DLA Piper when he was named, is suing PwC to have his retirement payments restored. Bersten left PwC in 2018 to fulfil a long-held desire to become a barrister. The decision wasn’t difficult, those familiar with his thinking say, because he had seen a noticeable ratcheting of sales pressure as soon as Sayers had become CEO in 2012.

Bersten and McNab have both gone into private practice.

Other leaders who were named by PwC in the wake of the tax leaks scandal fared differently.

After hundreds if not thousands of stories, millions of words and a reputational hit that reverberated around the world, the firm is humbled. That it is still having such difficulty rehabilitating its culture suggests there could be plenty more PwC headlines to come. As much as those directly involved may wish it, this is far from over.

Read more about the PwC tax leaks scandal

Part one | ‘We couldn’t believe it’: Insiders reveal how PwC unravelled as scandal broke The inside story of how PwC transformed from dull accountant into a sales-driven firm that would tear itself apart.

Part two | The emails that almost destroyed PwC Australia Insiders thought it was a “joke” for PwC to both advise the government on tax reform while helping clients exploit those reforms. One meeting sent the Tax Office over the edge.

Part three | The Tax Office goes to war with Seymour as Sayers goes big While PwC tax divisions was mired in a paper war with the Tax Office, the firm transformed from a conservative accounting firm to hard-charging, hard-drinking financial services company.

Part four | ‘I’ll make you more money’: Inside Seymour’s CEO pitch The candidates had unofficial campaign managers and developed manifestos. Lobbying was done in the office, over drinks, during the weekend. And like any good election, the voters’ main concern was what was in it for them.

Part five | ‘Nerds gone wild’: Inside PwC’s last party before it all blew up It is the days-long party now described as the last hurrah before the storm of the tax leaks. Within six months, the scandal would change the firm forever.

‘Potential conflict’: PwC kept in the dark for a year on CEO pay Kevin Burrowes’ second role with PwC International was the focus of the joint parliamentary inquiry into consulting on Friday morning.

Chanticleer | PwC hasn’t paid full price for eight years of risk failure Exactly who deserves the most blame for the PwC scandal remains a subject of fierce debate. But it’s the systemic failures of risk management that really matter.

‘This may not end well for you’: The secret war behind the PwC inquiry Documents tabled by three federal agencies raise questions about whether the ATO tried to shut down the investigation into the PwC tax leaks and targeted the man leading it, Michael O’Neill.

How confidential tax information was shared at PwC At least six former PwC partners were involved in leaking confidential information from Treasury, the Tax Office and Board of Tax, legal reports concluded.

PwC partner leaked government tax plans to clients The former head of international tax for PwC Australia, Peter Collins, has been deregistered by the Tax Practitioners Board for dishonesty and for sharing confidential government briefings with PwC partners and clients.

AFR journalists win Gold Walkley for PwC story Neil Chenoweth and Edmund Tadros broke one of the biggest stories of the year, which ultimately led to the break-up of the accounting firm in Australia.