Jozef Bajus is part of the Living Legacy Project at the Burchfield Penney Art Center. Click here to listen to his artist interview.

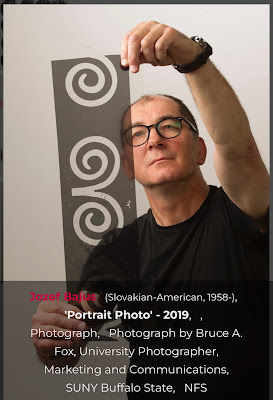

Jozef Bajus is an educator and award-winning mixed media artist and sculptor, working extensively with fibers, and assorted recycled materials. Born and raised in Slovakia, Bajus studied at the Academy of Fine Arts and Design in Bratislava, Slovakia, where he received both his BFA and MFA.

He began teaching at the Academy of Fine Arts and Design in 1990 during the Velvet Revolution, a time of major political transition for the country. Similarly, the institution underwent many changes, including the development of a Fibers program, led by Bajus.[1]

Since the implementation of the program, Bajus has held several teaching positions at colleges such as The Rhode Island School of Design, Slippery Rock University in Pennsylvania, Kanazawa College of Art in Japan and Jinxing University in China.[2]In 2002 he was appointed to coordinate the Fibers and Design Program at SUNY Buffalo State. Following the successful implementation of the program, Bajus continues to work at Buffalo State as an associate professor.

Although he has found much success as an educator, Bajus’s art has warranted him prestigious awards and international recognition. He was the first-place recipient of the Triennial of Pattern in Hungary, the Henkel Award in Slovakia, The George Soros Fellowship Award and the President’s Award for Excellence and Creativity from Buffalo State.[3]

Bajus has been featured in various solo and group exhibitions in galleries throughout the United States and Europe. His pieces are also part of the collections of multiple institutions worldwide, including the Szombathely Art Museum in Hungary, the Moravian Art & Craft Museum in the Czech Republic, the Slovak National Gallery in Slovakia, and the Gregg Museum of Art & Design in North Carolina. His works are also included in private collections in Europe, Canada, Japan and the US.[4]

Bajus was featured in the 2015 Art in Craft Media biennial exhibition at the Burchfield Penney Art Center. For his work, he was awarded the 2015 Langley Kenzie award, which is given to one outstanding artist from the Art in Craft Media exhibition and he was subsequently given his own solo exhibition.

Nothing is Going Away, which was on display at the Burchfield Penney from September 2016-March 2017, highlighted Bajus’s continuous focus on finding alternative uses for discarded materials. His use of repurposed materials connects to his overarching theme of understanding the environment, and society’s impact on it. The composition of his pieces displays complex relationships between these materials, and subsequently causes viewers to reflect on their own complex relationships with them.

One of Bajus’s central pieces in the exhibition, Acid Rain (2016) is constructed of wire tubing, metal and various hardware remnants. It closely resembles clouds and rain, reiterating the theme of environmentalism and our responsibility to the world around us.[5] His work makes viewers question how far their responsibility to the Earth goes, and if their job to protect the Earth is done once they've successfully separated the recyclables. According to Bajus, our impact on the Earth doesn't stop there. “Truth is, nothing is going away - everything stays, the same or in slightly different form, but it still stays, it’s around us.”[6]Because the impact of society’s waste is never-ending, Bajus’s pieces force viewers to contemplate if there are more useful ways we as a society can repurpose our waste.

Most recently, Bajus’s solo exhibition Gold Rush was featured at the Buffalo Arts Studio (2018). He has also been featured in The Corridors Gallery at Hotel Henry (2017, 2018), and was included in a group exhibition at the China National Silk Museum (2017).[7]

For more information, visit Bajus’s website jozefbajus.com, as well as his Buffalo State Faculty page, http://artdesign.buffalostate.edu/faculty/jozef-bajus.

[1] “About,” Jozef Bajus, http://jozefbajus.com/about/.

[2] “About,” Jozef Bajus, http://jozefbajus.com/about/.

[3] “Jozef Bajus,” Buffalo State Art and Design Department - Faculty,https://artdesign.buffalostate.edu/faculty/jozef-bajus.

[4] “Jozef Bajus,” Buffalo State Art and Design Department - Faculty,https://artdesign.buffalostate.edu/faculty/jozef-bajus.

[5] Elizabeth Licata, “Jozef Bajus at the Burchfield Penney,” Buffalo Spree, January 2017.

[6] Tina Dillman, “Jozef Bajus Solo Exhibit – Nothing is Going Away @ The Burchfield,” Buffalo Rising, Sept. 8, 2016.

[7] “Jozef Bajus,” Buffalo State Art and Design Department - Faculty,https://artdesign.buffalostate.edu/faculty/jozef-bajus.

CODA: The Village is Quiet (2021), by Patrick Hartigan

Patrick Hartigan (b.1977) is an artist who has work held in a number of public collections including the National Gallery of Australia, the Museum of Contemporary Art, the Art Gallery of New South Wales, the Auckland Art Gallery, and the Art Gallery of Western Australia. But the website at Gazebo Books also tells us that he sometimes combines visual artworks with short fiction:

In 2009 he created a series of paintings, films and short stories, collectively titled The Village is Quiet, based on the experiences of living in the village of birth of his wife Lenka Miklos, in the Spiš region of Eastern Slovakia.

The Village is Quiet takes us into a completely different world. In a series of short, interconnected vignettes, Hartigan describes the simplicities of rural village life that seem timeless, at least superficially so. Even the remnants of the old Soviet propaganda infrastructure have merely changed to play local news on a scratchy radio, but there’s no sign of the interconnectedness of contemporary life. Global commerce and consumerism doesn’t take second place to mend and make do — there’s no sign of it at all.

From the perspective of an affectionate outsider with limited command of the language, the narrator participates in the life of the family as best he can, sometimes to the amusement of others who recognise that he doesn’t have the skills that are second nature to them. (Like a child, for example, he is not allowed to use a scythe to cut the hay, for fear he might cut himself.)

He describes details of the meals because they are new to him, and so is the experience of butchering Grandpa’s goats. This is small farm, semi-subsistence living and as the text progresses, the reader understands why Grandma in the opening pages is anxious when one of the goats in season refuses to mate but she has to pay the goatherd for the service anyway.

Apparently the goatherd lives on stale bread but grandma says she’s seen him feed fresh bread rolls to the fish in the creek. The walls of his house have large cracks from where moisture has entered and frozen, year after year. He used to have an older woman from the neighbouring village living with him; she was sick and he was looking after her. Then she died and he couldn’t afford to pay for gas.

After ten minutes or so — the yard now completely dark — we give up. Grandma hands the man a folded twenty-crown note for his time. In a loud voice he tells her to take the goat to the neighbouring village where there’s another male goat; as he talks his eyebrows appear wild and erratic. He shrugs his shoulders and closes the gate. Grandma drags the uncooperative goat down the dark road, the headlights of passing cars exposing her worried face. (p.5-6)

We learn that Grandpa’s age is affecting him in more ways than one. He’s mending a torn glove when they get home, but he doesn’t stop when Grandma delivers the news.

He asks a few questions, then embarks on one of his meandering tales. The story begins with another man who has a male goat, then meets up with the wife of a male relative and eventually climaxes around a man nobody seems to know. (p.6)