How do we really see interior design? Where do we experience new trends, looks and vibes? How many of us actually spend time in top-end showrooms, visit the outrageously stylish apartments of friends or are invited to weekends at stately homes or Italian palazzi? Well, OK, this is the FT, so maybe some of us, but I’d suggest that for the most part, we encounter those interiors that most influence us — whether consciously or not — at the movies or on TV. We discover domestic design vicariously via the screen.

After all, these fictional interiors have been as carefully curated as any furniture showroom or professionally designed penthouse — because they play a crucial role in visual storytelling. Sets construct stories as well as physical spaces and rooms reveal facets of character before that character has even appeared on screen.

The paintings, the books, the pictures on the wall, the kind of desk or the things placed on that desk all subtly build a back-story.

The individual items and the designs of interiors situate us in time, in taste, in class, in money.

Think of Holly Golightly’s apartment in Breakfast at Tiffany’s, a spare, modern interior with a cutaway bathtub for a sofa, with stacks of suitcases or boxes for furniture, as if to suggest it could all be moved in a moment — this is a woman with no roots, still struggling to define who she is.

Or take the shadowy interior of Vito Corleone’s study in the opening scene of The Godfather: the big desk, the film noir blinds, the darkness in the middle of a bright day, the blend of family and work, at home and in the office.

I used to have a particular bugbear about Modernist interiors and furniture in the movies always used as a cipher for evil: sleazebags, crooked financiers or super-villains.

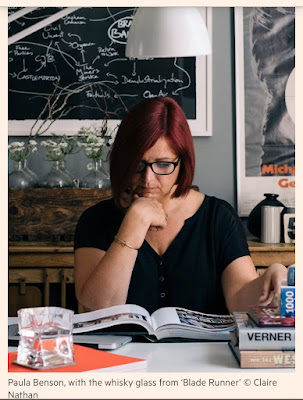

Black leather Mies van der Rohe chairs, Le Corbusier loungers or LA modern houses all seem to augur something sinister. “Perhaps we all want a bit of Bond villain’s lair,” says Paula Benson, founder of Film and Furniture, which helps cinema buffs identify and buy the pieces they have seen on screen. “Those rooms just look so good.”

Like Benson, I also scan the movies obsessively for details. And, she admits, it can ruin a film when she’s constantly checking out the props.

“People hate watching with me because I’m always pausing to look at some detail. I watch everything twice, first to look at the furniture, then to watch the film.” Those details are deeply considered, says Sonja Klaus, a London-based film and television designer.

“What we do is not interior design,” she says. “When I’m designing a set for a character’s home I like to think I become that person.” More like Method acting — in design — then? “Yes, I suppose so. It’s not thinking where would he put his glasses down but where would I?”

Among Klaus’s projects was the dark BBC drama series Taboo, starring Tom Hardy. “This was a man who had returned and inherited his father’s house so he was living with things that were not his, that already had a character,” she says. “The best thing anyone can say to us is, ‘Where did you find that location?’

When actually we’d built it all in a studio. Hardy kept running his fingers over the surfaces asking if it was real.” Judy Ducker, a set decorator and production buyer who has worked on big productions including Martin Scorsese’s Hugo, says the hardest films to get right are the ones set in the recent past “because we remember what things looked like”.

“I worked on the Diana movie and we could get the decor right but the technology was difficult — to get the right mobile phones or those beige computers.” What she touches on is critical because most of us live with a mix of things, some old, some new; we rarely buy everything at once.

As a result, interiors are rarely entirely of their time, they are hybrid. Wes Anderson’s production designer Adam Stockhausen captured this mix well with The Grand Budapest Hotel, an interior from a golden fin-de-siècle of somewhere-in-central Europe but one that was clearly added to in the 1970s with its oranges and browns.

Stockhausen suggests that those distinctive colours were inspired by minor props such as metal ashtrays — the smallest items can define entire sets.

There's a real loyalty to Kubrick and people want to cement that love of his films

with something real

99 — Paula Benson, founder of Film

and Furniture

Nothing on a Stanley Kubrick set was random. “He wasn’t the kind of director who would just pick something from a prop store,” Benson says. “He wouldn’t have used something that had been used by another director.” If our most immersive experience of interior design comes from film and television, how does it affect us as viewers — and as consumers?

When Benson watched Kubrick’s The Shining, she became entranced by the geometric carpet that appears in the shots of young Danny (son of Jack Nicholson’s writer) playing in the corridor of the Overlook Hotel. After visiting the Kubrick archives, she eventually found the carpet had been designed by interior designer David Hicks.

Hicks had been very much a part of the London scene in the 1970s, working for aristocrats, boutiques and bohemians, and Kubrick would have been well aware of his work.

So the carpet might have been slightly out of place in the Rockies, where the exterior was set, but the interiors were shot at Elstree Studios at Borehamwood, just beyond the northern edge of London and near Kubrick’s home. People may recognise and admire the pieces from the movies, but do they really buy them?

Who has a Kubrick carpet (the pattern of which is actually called Hicks’ Hexagon)? “Oh you’d be surprised,” says Benson, who sells the officially licensed version of the carpet. “People have it in their homes, in hotels, as a statement. Loads of them seem to go into home cinemas.” (A double homage, then.) Is it a kind of code, I suggest, a conversation piece? “Big time. There’s a real loyalty to Kubrick and people want to cement that love of his films with something real.

They may not consciously be watching films for [interiors] inspiration, the link may be subconscious, but it is still there.”

It is not just the carpet. Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey made an impact too, with Olivier Mourgue’s low-slung Djinn chairs, the still-futuristic-looking pieces that appear in the Hilton space station scene, and the Arne Jacobsen-designed cutlery, “which still looks amazing”, Benson says.

The movies, from historical dramas to sci-fi attempts at predicting a future, inevitably reflect and intensify the present. The industry has the resources to use the best and newest designs and the production designers, set dressers and prop consultants who are most keyed in to contemporary trends and the coolest new things. And those images then broadcast and amplify trends. But are set designers and prop buyers tastemakers themselves?

Can they change the look of our lives? Benson says Mad Men had a huge impact. “Mid-century modern was already an interest but that series really pushed it forward — the Florence Knoll sofas, big table lamps . . . Nordic noir, Borgen and The Bridge were a big reminder of how beautiful Scandinavian design was, the Hans Wegner dining chairs and the Poulsen lamps.”

She might also have pointed to the slightly darker version of the era portrayed so atmospherically by Tom Ford in A Single Man, in which a bereaved Colin Firth plans suicide in an exquisitely rendered world of Modernist shadows cast by the Schaffer Residence, the John Lautner-designed house in Los Angeles where the film was shot. Ducker says the long-running TV adaptation of Agatha Christie’s Poirot (1989-2013), on which she worked, “definitely made Art Deco more popular. Specialist dealers in Deco were saying to us that the series had done them a favour.”

“Sometimes you see the influences more in fashion, for instance Peaky Blinders had a real impact on menswear but I also think the success of Game of Thrones reintroduced the gothic,” she says. She also cites TV series Bridgerton: “It’s not for me but I do think that rather camp, over-the-top version of Georgian has had an impact. All those pastel wallpapers.”

That colour-saturated aesthetic might also owe something to Wes Anderson, whose obsessive visual sense pervades his movies and has filtered outside. The candy shades of The Grand Budapest Hotel can now be seen in east London patisseries or Brooklyn gelaterias.

Anderson and Stockhausen are a relatively rare example of direct influence; usually it is more subtle.

Many architects are inspired by the movies, but largely it happens subconsciously. Architect Adam Richards is unusual in attributing elements of his own house, Nithurst Farm in Sussex, to specific films. Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker, a bleak, apocalyptic vision of a toxic landscape, might not seem the cosiest inspiration for a domestic interior.

Yet “our main kitchen space is quite closely modelled on an interior in Stalker,” Richards says, referring to a scene in which a hallucinatory, post-industrial space stands in for a kind of heaven. “The house embodies a journey — and this was a destination, a space about faith and doubt.” I paid a visit to the astonishing warehouse of one of the UK’s leading prop specialists in west London, which preferred not to be named here. These places are often described as Aladdin’s Caves but it was more than the kitsch cocktail suggested by that label.

This was a museum, with rooms full of Renaissance pieces and Rococo furniture, oddly familiar pieces such as the bust Joaquin Phoenix strokes in Gladiator or a slightly dusty, fussy sofa that Marilyn Monroe reclines on in The Prince and the Showgirl. ‘Poirot’ definitely made Art Deco more popular. Specialist dealers were saying to us that the series had done them a favour Judy Ducker, a set decorator and production buyer

In this cornucopia you can see the designers’ dreams for Saltburn or Call Me by Your Name, the louche decadence embodied in collections of big, old and beautiful things, objets d’art that frame an idealised lifestyle in a palazzo or a mansion. They represent a kind of stasis, an inherited sense of grandeur which looks likely to come to a sticky end. Yet it is also the smaller things — the personal items, the artefacts employed in an intensely emotional scene — that matter arguably more than the grand gestures.

Among the homewares for sale on Film and Furniture’s website is the whisky glass from Blade Runner: a square, slightly cinched glass designed by architect Cini Boeri in 1973 and used by Ridley Scott in what has become the ultimate dark sci-fi classic. Still manufactured by Arnolfo di Cambio, it has become a bestseller on Benson’s site.

After all, why wouldn’t you want to drink from the same glass as a depressed dystopian AI assassin? As well as combing cinema classics for the designs that appeal to viewers for their own homes, Benson has to anticipate the next film or TV series that might shift our tastes in home decor.

So which sets are we responding to now? She has her eye on Netflix’s recent adaptation, Ripley: “It’s quite slow, so there’s plenty of time to look at details but I did notice all those wonderful desk sets, the paraphernalia of writing, which is something we don’t do any more.”

Perhaps next we will all be yearning for inkwells, fountains pens, blotters and leather-topped writing desks. Creating characters for ourselves, just like they do in the movies. Edwin Heathcote is the FT’s architecture and design critic