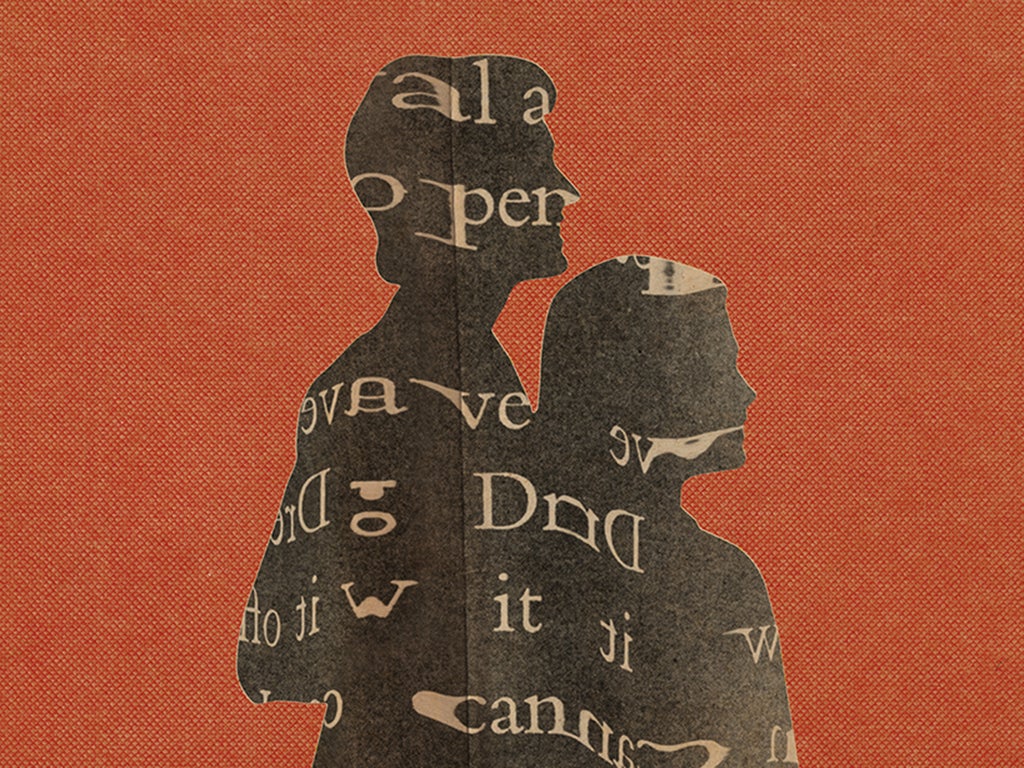

In search of a language of loss

Is there a correct way to mourn? When my mother died, I scoured the literature of grief for answers

The night before my mother died, she threw a cocktail party. It was her 73rd birthday and she knew she was dying. The 20 or so friends who gathered in her flat knew she was dying, too. But Mum didn’t want to talk about it. She insisted on manoeuvring her stiff, shrunken arms into a sparkly jumper and backcombing her hair the way it was when she was a teenager. She wanted to drink Gin & Its – or more precisely, she wanted us to drink Gin & Its, since all she could manage were tiny sips of mango juice.

By lunchtime the next day, all the guests had trickled away. Mum’s best friend, my brother and his wife had left Bristol for London. My husband had also left to take care of our two young children. “I can come back with the boys,” he said, to which I replied, a little too tersely: “One-year-olds and syringes do not mix.” In truth, I was scared. I had never seen anyone die. Now I was alone with my mother, an oxygen machine and a fridge full of leftover party food.

I had given birth only the summer before, and the experience of watching her face death had much in common: my mother’s emphasis on breathing, her look of helpless pleading and then supreme focus. She was in the zone. She was barely able to speak but her face flashed with past, more energetic selves: the school running champion winning the county race; the English teacher holding court; the political firebrand addressing the rally.

We were lucky: we had managed to get Mum out of hospital – apart from everything else, it meant that she could retain her near-religious faith in the NHS– but we had no professional care in place. Just friends. Julia, a former nurse, came by to help me administer morphine. My friend Sarah, a doctor, drove over with a suitcase of my clothes so I could stay the night. My mother, sitting on the sofa, one leg tucked protectively underneath her, looked desperately relieved to see her. We stepped out of the room to discuss how to move Mum into her bedroom – and in these two or three minutes, she died. Lung failure, heart failure.

We toasted her with prosecco and some macaroons she had been given as a birthday present. It was the best way to remember her, Julia and Sarah agreed. It was also a sedative for the shock of losing your mother on a cold December night. Then the three of us lifted Mum’s tiny, contorted body from the sofa to her bedroom. Julia’s jumper snagged on a door handle. “Hang on! Stop! We need to reverse.” They didn’t want to be the first to laugh so it was down to me to get the giggles. “Mum would have found this hilarious.”

Would have. She had been dead less than an hour. I now realised that the last thing she would have seen were her still-wrapped birthday presents, piled up around the fireplace.

“The layers of loss make life feel papery thin,” writes the novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie in Notes on Grief (2021), her spare, lyrical outpouring of sorrow. Adichie’s 88-year-old father, James Nwoye Adichie – Nigeria’s first professor of statistics – died suddenly when she was thousands of miles away in the US and couldn’t get back. Two aunts died shortly afterwards, prompting a “sensation of eternal dissolving”. For Adichie, the physicality of her own grief also recalled the experience of birth, of pushing out a child.

I was given Adichie’s book by a friend of Sarah’s who had lost her mother to Covid-19; she had heard that I had lost my mother and grandma within a few months of each other. This is the kind of activity that goes on among the bereaved, I discovered, the passing of books, poems, lines. I suppose it’s because we are searching desperately for language to describe the peculiar transition from being to not being – metaphors and similes that borrow imagery from something generally understood (a tidal wave, a cliff edge, a dark tunnel) to help explain something bewildering. And it was books that provided the bond between me and Mum, who had been an English teacher, and didn’t feel the need for many other possessions.

[See also: In this time of conflict, I recall my late mother’s Christian wisdom and kindness]

In her memoir about the death of her father Lost & Found (2022), the journalist Kathryn Schulz uses a wonderfully vivid metaphor to explain how sorrow is assailed by something more complex: her grief, she writes, manifested as anxiety, irritability and distraction; her sadness was more “furtive” and “vulnerable”, like “a small neutral nation on a bellicose continent whose borders were constantly overrun by more aggressive emotions”. Like me, she longed to experience a purer grief, yearning for “moments when my sorrow ran through me like a river at night, dark and clear, untainted by any more insidious emotion”. Yet, as she acknowledges, “such things aren’t responsive to our wishes”.

After my mother’s death, it was Adichie’s depiction of loss as “an erosion” that resonated. “Grief is a cruel kind of education,” she writes. “You learn how much grief is about language and the grasping for language.” I kept reaching for my own figures of speech, only for them to writhe out of my hands. It was as if a building had been demolished, leaving a gap in the skyline. It was a tape that had… just stopped. Writing about her was easy: she was so distinctive. But writing about my relationship with her – this was a slippery business.

My mum, Annie Thomas, wasn’t famous, but she was well-known to the thousands of children she had taught, and to seemingly everyone involved in left-wing politics in Bristol. Born to working-class parents in Gosport in 1948 – the same year as her beloved NHS – she was a Labour councillor when I was growing up, known as “Red Annie” in the local press, and thrown out of the party for disobedience in the early 1990s. She remained fiercely committed to feminist and socialist causes – one of my childhood holidays took place at a Socialist Workers’ conference in Skegness – and eventually returned to the fold as chair of the Bristol West Constituency Labour Party when Jeremy Corbynbecame leader. She was, as many of her friends said, a fighter, a powerhouse, “the best MP we never had”.

You didn’t want to get into an argument with my mum. She was courageous and uncompromising. My childhood memories involve picket lines of all kinds, Free Nelson Mandela T-shirts, Mum appearing on the local news in a shock of peroxide, declaring she was prepared to go to jail over the poll tax. She did all this while bringing up me and my brother alone, on a teacher’s salary, having divorced my father when I was three. One of the final things I said to her, minutes before she died, was, “Mum, you are so brave.”

But she could be tough on me. I was her eldest child, her only daughter. If there was a misplaced word or an inflection that didn’t quite align with her mood, there would be a flare-up. She often thought I was sneering at her, and I felt she was trying to control me. In The Cost of Living (2018), the second part of her “living memoir”, Deborah Levy writes about the death of her mother, a woman who was (like mine) “braver in her life than I have ever been” but who (also like mine) “gave me a hard time, beyond the call of a dutiful daughter”. Levy quotes Marguerite Duras saying she believes “the mother represents madness. Our mothers always remain the strangest, craziest people we’ve ever met.” But, Levy adds: “Now I can see that I did not want to let her be herself, for better or worse.”

That was true of me, too. Mum was forthright, rebellious, embarrassing. She once smuggled us onto a train from Prague to Paris without paying and made us hide from the inspectors. She was a conscientious objector to all domestic tasks, and one Christmas fell out with a friend who bought her a recipe book. At parties, she got up on chairs to dance and when she went to the theatre, which she loved, she would buy the cheapest standing tickets – before making a dash for an unoccupied seat in the stalls after the interval.

And yet she developed an extensive network of devoted friends. She was single for the last 35 years of her life but one of the least lonely people I knew, having dispersed any need for companionship, affection, humour, intimacy and adventure among dozens of friends. “Life was always exciting with Annie,” one wrote to me after she died. My husband adored her. To my children, she was the most radiant and magical grandmother. But what was she to me? Levy describes her mother’s body as her first “landmark”, a disorienting thing to lose. “Most childhood memories were twinned with her presence on earth.” To me, my mother was beautiful, fierce, familiar. But how much easier to remember her as she was to others.

Even the undertaker, it turned out, had known her. “You’ll want to do something that includes all her friends in politics,” she said. And I did feel this responsibility deeply. When two of her comrades refused to attend her funeral, preferring to commemorate her in their own way, I fretted to one of her older friends that I was misremembering her somehow. “No, Jo,” she replied. “She was your mum.”

[See also: Nick Cave: I don’t think art should be in the hands of the virtuous]

She repeated this phrase again and again until the strange, incantatory rhythm broke down my defences. Someone gently led her away when I started crying. It took me back to being a child in the dark at night, listening for the sound of my mother’s car returning home from a Labour Party meeting. Waiting for her to open the garage door beneath our house, greet the babysitter, put the kettle on. How long would it take her to come upstairs? Would she go to my bedroom first? She was your mum. She was your mum.

In Clover Stroud’s The Red of My Blood(2022), about the death of her sister, Nell Gifford, the leader of a circus troupe, the author wonders what is an “appropriate” way to remember the deceased. She admits to being transfixed by her 46-year-old sister’s “golden” dead body. She wonders if taking photos of it was “extremely weird”, yet was happy to have that image on her phone whenever she felt strong enough to look at it.

I did the same, partly for my brother (who then told me he never wanted to see it), partly for myself. A month later, when my best friend’s father died in India, she sent a photo of him wrapped in cotton lying in a refrigerated casket on his porch. I sent back the image of my mum covered in a patchwork quilt made by a friend, next to the roses Sarah placed beside her. We had both loved each other’s parents.

That night, I held Mum for as long as I could bear. Too often, I had flinched from her, anticipating some kind of criticism, but now I focused on her hands, the only part of her body that still felt familiar. We used to hold hands while watching the news. We held hands when I was in labour with my first son. It was a relief that she had gone after so many years of pain, a relief she hadn’t died in a hospital corridor, a relief that I didn’t have to preside over another spiralling situation.

In Ian McEwan’s novel, Lessons (2022), his protagonist Roland expresses a similar desire to hasten the passing of his mother. He struggles to remain present at the deathbed. Watching her stooped figure in the care home, he supposes “he would not see her alive again but after ten minutes that did not stop him wanting to leave. On the contrary. As he saw it she was already dead and he was already grieving but could not do it in her presence.” Lessons was perhaps the first novel published after my mum’s death that I knew she would have read and discussed with me – not least because it followed a man also born in 1948 to a working-class family. It was both cathartic and agonising to read, a reminder that the baby boomers weren’t, as we had once joked, immortal.

Five years before, when my mother was seriously ill, I had read Emily Berry’s poetry collection, Stranger, Baby (2017). Berry’s mother died when she was a child, and one line haunted me: “A mother’s death lasts a lot of years”. When I realised my mother would never get better, and that she would always remain inscrutable on the subject of her own death, I began privately rehearsing the moment I would lose her – often in the shower where my family couldn’t hear me crying. I would repeat to myself: “My mother is dying, my mother is dying.” I began reading more about death because I could see it coming.

And yet I’m not sure how useful this anticipatory grief is. For some time after Mum died, I still woke up thinking: is that it? All the richness and noise and struggle and force of personality. She must have had some kind of plan? And even if she has gone, surely this elaborate enterprise she had got up and running – all these people, all these beautiful and strange connections – isn’t just going to pack up and go home?

I felt a pressure to preserve her world, to maintain all the conversations, to hire some sort of brilliant stage manager to “keep the ball rolling” as Joseph Conrad had it in his novel Chance. Unlike my best friend’s father, an artist and writer, she left no material legacy. I have her books, some newspaper cuttings and a cup we had made with her face on it. Every now and then, when I go to reheat my coffee, I am faintly aware that I am pulling my mother out of the microwave. Would she approve? Am I doing this right?

In Sheila Heti’s novel Motherhood (2018) her narrator reflects on the inevitable entanglements with our mothers and grandmothers, and advises women not to struggle against them. “How far beyond your own mother do you hope to get?… Let the pattern which is the repeating, which was your mother, and her mother before her, live it a little bit differently this time. A life is just a proposition you ask yourself by living it, Could a life be lived like this, too?”

By far the weirdest aspect of grieving is how much I have come to like images of myself, simply because they remind me of her. I used to be so self-conscious – and the vain part of me is horrified by how much grief has aged me (Schulz calls it: “all at once, one very large step into oblivion”). But I rather like the fact I now look a bit like my mother did. I find I am not fighting it.

Johanna Thomas-Corr is literary editor of the Sunday Times

[See also: Kenneth Roth: “My biggest concern is for academic freedom]