I think you have to have the bad days, so you can love the good days even more

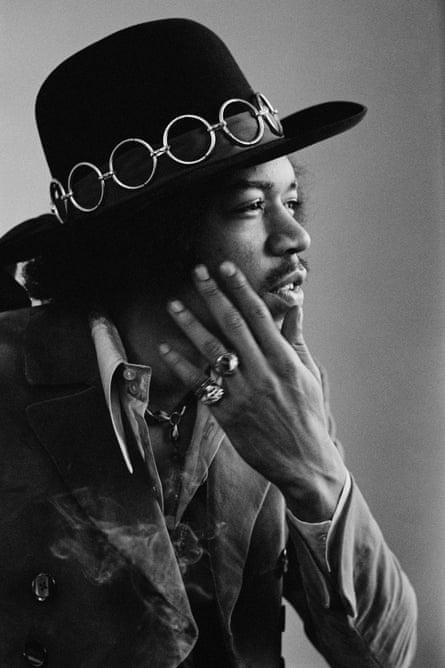

‘COLORFUL, VIBRANT, SENSUAL:’ Stars on Jimi Hendrix, 50 years gone.

And back in his day, far too colorful, vibrant and sensual for some: Micky Dolenz recalls ill-fated Monkees tour with opening act Jimi Hendrix: ‘Yeah, it was kind of embarrassing.’

This week alone he has published at least two essays -- “Fame” in Commentary and “Style Reveals the Man” in First Things. In the former he writes:

“For me the true pleasure in writing is found in the work itself: in the delight in amusing phrases, well-turned sentences, rhythmical paragraphs, conclusions I had little or no idea I would arrive at until my composition was complete. I have long subscribed to E.M. Forster’s remark, when asked his opinion on a subject, that he didn’t really know what he thought until he had written about it. Writing, in this view, is an act of discovery, and so it has been for me.”

In 1974, C.H. Sisson freely translated Horace’s Epistle II.3, Ars Poetica, as The Poetic Art. He writes, in part:

“The man who can actually tell when a verse is lifeless

Will know when it doesn’t sound right; he will point to stragglers,

And equally put his pen through elaboration;

He will even force you to give up your favourite obscurities,

Tell you what isn’t clear and what has got to be changed,

Like Dr. Johnson himself. There will be no nonsense

About it not being worth causing trouble for trifles.

Trifles like that amount in the end to disaster,

Derisory writing and meaning misunderstood.”

Copy for a high-school radio station and its podcasts isn’t poetry. At least it shouldn’t be. But it’s never too early to learn the importance of clean, clear, concise, precise prose. It is “worth causing trouble for trifles.”

While he had been making The Color of Money a few years previously, Scorsese took time away from Tom Cruise’s increasingly dazzling smile to read a non-fiction book by Nicholas Pileggi, Wiseguy. Pileggi’s beguiling and revelatory account of the everyday life of the New York Mafia appealed to Scorsese for its procedural aspects as much as the opportunity to make a gripping and visceral piece of cinema, and so he telephoned the writer in an attempt to purchase the rights. In the retelling, their conversation has something of the mythical nature of Stanley meeting Livingstone: Scorsese told Pileggi, “I’ve been waiting for this book my entire life”, to which the understandably overwhelmed writer replied, “I’ve been waiting for this phone call my entire life.”